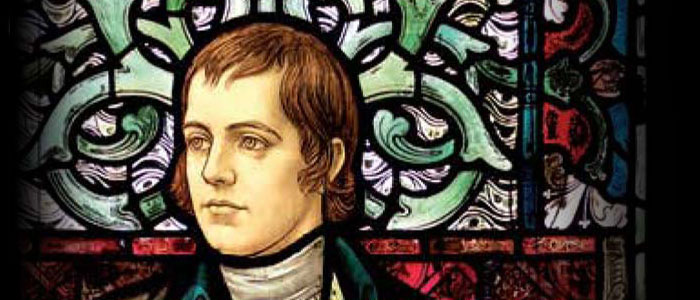

On 24 January, 2017, the Centre welcomed Dr. Gerard Carruthers (University of Glasgow) to discuss ‘Robert Burns, Glasgow, Song’. In this seminar, he described the historic context of several of Robert Burns’s poems and songs and how each related to the poet’s connections in Glasgow. Gerard was joined by Alison and Fiona McNeil of the band Reely Jiggered, who performed the songs featured in Gerard’s talk. Below is this listener’s summary of the lecture.

Prof Gerard Carruthers began by saying that although there are only five recorded visits of Robert Burns to Glasgow between 1787 and 1791, his relationship with the city is still important. He associated with many people from the city, especially those who were affiliated with the University of Glasgow. In the 18th century, the institution was largely moderate Presbyterian in theological leanings. The context that Carruthers provided for these songs demonstrated Robert Burns’s moderate Presbyterian beliefs.

In “Holy Willie’s Prayer,” 1785 Burns attacked both Reverend William Auld of Mauchline, who had attended the University of Glasgow, and William Fisher, who had accused Robert Burns’s friend Gavin Hamilton of lax church attendance and misappropriation of the poor fund. While this poem was not published in his lifetime, it was circulated throughout the Ayrshire countryside as poetic justice against William Fisher, whose accusations against Hamilton were declared to be unfounded. In his analysis of this poem, Gerard stated that we can see the moderate Presbyterian beliefs versus those of the Popular party. He described the poem as propaganda; the way Burns portrayed Rev. Auld does not appear to be entirely true. Contemporary sources suggest that William Auld was actually quite kind to Robert Burns, particularly when he was accused of fornication.

Reverend William Auld makes another appearance in Burns’s 1789 song, “The Kirk’s Alarm”. Although Burns had moved from Ayrshire, church politics still feature prominently in his work. In this song, Auld is described as a windbag who makes a lot of noise, but has no teeth. If the contemporary sources are a more accurate description of Auld, Carruthers argues that this is likely more propaganda in which Burns distorts the personalities of others to make a point. Burns wrote this poem in defense of William MacGill, who was also an alumnus of the University of Glasgow and had been accused of heresy. MacGill was a well-regarded theologian who wrote an essay on the death of Jesus Christ, which was criticised heavily by the hardline Calvinists, as they believed that he had downplayed the crucifixion. It appears that Burns used a secular piece from “The Glasgow Mercury” as a structural model for “The Kirk’s Alarm” and reworked it to apply to this theological issue. Gerard also argued that this situation with MacGill is evidence that Burns and Thomas Muir were not close, contrary to popular belief. Muir was a member of the popular party and was the prosecutor against MacGill in this case.

The Glasgow connection for “A Man’s a Man for A’ That,” is that it was published in The Glasgow Magazine. However, it is unlikely that Burns approved of the dangerous version that this magazine published. “A king can mak a belted knight” was written instead of “A prince can mak a belted knight.” During the 1790s, the government was looking for any contempt for the king; violators could be accused of sedition. It is far more likely that someone else took his poem and radicalized it. The Glasgow Magazine only ran for five months, and all twelve poems published in this publication were also published elsewhere. Carruthers found it very unlikely that Burns would have sent this poem to a radical Glasgow magazine; he would have been more cautious.

While there are several Glasgwegian women that Burns wrote about, he appears to have fancied two of them. Agnes Maclehose sought to meet Burns in 1787. According to Carruthers, it appears that Burns first thought that she was some sort of “groupie”; subsequent letters between the two suggest that they had developed a physical relationship. He married Jean Armour a year later, but there is a record of him making one last visit to Agnes Maclehose in Edinburgh in 1791. From this last meeting with Agnes came the song “Ae Fond Kiss.” The second Glasgwegian woman who Burns appears to have lusted after was Wilhelmina Alexander, who was born in Paisley but whose family owned a house off George’s Square. He composed the song “Bonnie Lass of Ballochmyle” for her, but after he sent it to her, her family deemed it too risque and discouraged him from publishing it.

“Auld Lang Syne” has a more modern connection to Glasgow; the University of Glasgow set the world record by assembling more than 200 people to sing “Auld Lang Syne” simultaneously in 41 different languages in November 2009.

Summary by Megan Kasten (PhD Researcher)

Our seminar series continues next week on 31 January 2017 with Dr Sheila Kidd (University of Glasgow) for a launch of her new book, ‘Còmhraidhean nan Cnoc. The Nineteenth Century Gaelic Prose Dialogue’. This will be held in Room 202 of 3 University Gardens at 5.30pm. All welcome!