On 13 May 2014, the Centre was pleased to welcome Dr Kate Louise Mathis (Aberystwyth University) to discuss ‘”An Ideal Wife?” Alexander Carmichael’s Deirdire & Revivalist ideals of beauty, dignity & death’. Below is this listener’s brief summary of the lecture.

Alexander Carmichael’s rendition of the story of Deirdre first appears in the Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness (1888/9) and is an adaptation of the tale collected by Carmichael from an elderly man, John MacNeill, from Barra in 1867. His version of Deirdre differed significantly from the one presented in Longes mac N-Uislenn (‘Exile of the Sons of Uisliu’) which dates back to c. 900 (or earlier) and is found in manuscripts including The Book of Leinster (begun c. 1160). The original Deirdre is characterised almost entirely by her passivity–she is a blank slate–and the story itself is concerned as much with the exile of Fergus as it is the deaths of the sons of Uisliu and Deirdre. Her passivity made her attractive as a ‘vehicle for reshaping’.

The seventeenth century Irish poet and historian Geoffrey Keating was the first to emphasise the romantic love of Naoise and Deirdre, making it the focus of the story. He also dissociated the exile of Fergus from the tragic deaths of the two protagonists.

By the nineteenth century, Deirdre had become an exemplar for tragedy and a touchstone for expressions of grief and mourning. By this stage she was the central female figure in Irish mythology and Longes mac N-Uislenn became ‘her story’. Writing in 1983, Alan Bruford commented:

[The story is] the death of the Sons of Uisliu, and it is only literate sentimentalists who see it as Deirdre’s story.

The Glenmasan manuscript, compiled c. 1500, also detaches Deirdre and the sons of Uisliu from Fergus, while expanding the careers of Naoise and his brothers in Scotland. Previously, the inclusion of Scotland in the story was vague at best, with no mention of place names or the name of the king who employed the sons of Uisliu. This suggests the (unknown) author of the Glenmasan manuscript was familiar with Scotland, particularly Argyll.

Carmichael’s version is similar to Keating but again embellished the exploits of the sons of Uisliu. He also expanded the sparse mention by John MacNeill of Fergus negotiating with the sons of Uisliu in Scotland with a twelve page interpolation of this episode. (This may have derived originally from the Glenmasan manuscript). Dr Mathis noted that the dignity of Deirdre in Carmichael’s text derives from his interference with the oral text provided by John MacNeill.

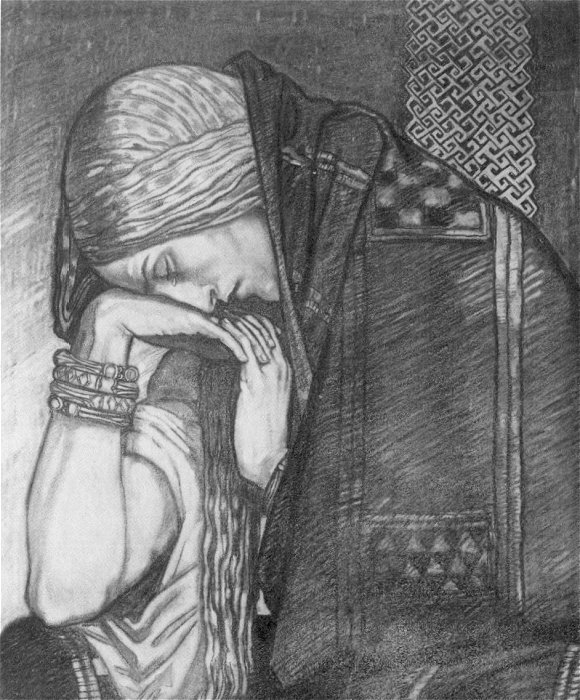

During the Celtic Revival (1880-1920) the character of Deirdre became ever more exaggerated as unparalleled in beauty and wisdom. W.B Yeats included Deirdre’s children in his version, claiming in a letter to Lady Gregory that…

…the children will improve the tale of Deirdre by giving one a better and fuller feeling of her married life in Scotland…[she] is the normal, compassionate, wise house-wife lifted into immortality by beauty and tragedy. Her feeling for her lover is the feeling of the house-wife for the man of the house.

William Sharp, writing under the pseudonym of Fiona MacLeod, made Deirdre semi-divine, made from ‘dusk and ivory’. In her version, Deirdre gives Naoise a yellow thistle as a sign of her love, which will become her shame should he reject her. Dr Mathis suggested this was a way of toning down Deirdre’s offering herself to Naoise, which often had her appear nude. MacLeod also tones down the gore-factor: instead of Deirdre drinking the blood from Naoise’s severed head she cleans the blood and kisses his lips. Furthermore, her own death is not recorded. Fiona MacLeod commented in the preface to ‘Deirdre and the Sons of Uisne’ (1903):

Children, and maids and youths…have had their loves deepened in love and devotion because of this tale of endurance noble to the end, and of patience so great that the heart aches at the thought of it.

Murray Pittock described neo-Jacobitism as representing ‘symbolic beauty, perfection and death’ and Dr Mathis suggested this could easily apply to Carmichael’s Deirdre.

Summary by Ross Crawford (PhD Researcher)

Our seminar series continues on Tuesday 20 May with Prof Thomas Clancy’s ‘How British is Scotland? Celtic Perspectives on Multiculturalism’. This will be held in Boyd Orr Lecture Theatre 1 at 5.30pm. All welcome.