On the 5th of November the Centre held a book launch event, presented by Dr Alice Blackwell (National Museum of Scotland) and Dr Ewan Campbell (University of Glasgow, Archaeology). Dr Blackwell introduced their new edited volume Scotland in Early Medieval Europe. The book is free to read online, available in PDF and is print on demand in both paperback and hardback, published by Sidestone Press, Leiden, the Netherlands, available via https://www.sidestone.com/books/scotland-in-early-medieval-europe.

The aim of this publication was to explore early medieval Scotland in a contemporary European context and promote Scotland’s material culture and research to an international audience. Dr Blackwell drew attention to the book cover, the 8th century carved stone cross-slab from Hilton of Cadboll, Easter Ross, which was chosen as an effective visual summary of the contents of the book as well as the cultural connections and processes that represent the early medieval period in Scotland. The volume features archaeological, artefactual, historical, and place-name evidence from this period, which reflects the cross-disciplinary research community in Scotland. Short and wide-ranging contributions from period specialists discuss everything from artefact fragments to burials and monuments, places, landscapes, and ideas. The volume is well-illustrated and designed as an introductory overview and summary of the period to unfamiliar readers as well as presents new research and long-term projects from across Scotland. The contributors hope that this publication becomes exemplary in its range of topics, presentation and availability, inspires new confidence in early medieval research in Scotland and helps promote it in the international sphere. The book is dedicated to the memory of Dr Alasdair Ross.

Dr Ewan Campbell continued the talk presenting his contribution to the volume, titled “Peripheral vision: Scotland in Early Medieval Europe”. In the paper, he explores ideas of periphery and liminality of Scotland in the early medieval mind. In the medieval worldview, Scotland was “at the ends of the Earth” as expressed by Adomnan. This is illustrated by the medieval Mappa Mundi where Scotland in right on the edge of the known world. This peripheral location of holy places like Iona was significant to the religious mission of monks in spreading the Christian gospel to distant corners of the medieval world.

Dr Campbell’s aim was to shift the view from this periphery onto the continent to reveal that Scotland was actually at the crossroads of marine travel with access to large parts of Europe. In this sense it was not peripheral but quite central. He began by quoting several comments from some scholars who envisioned medieval Scotland as a state that failed to integrate and develop its simple and inferior culture (namely Hodges 2004, Pinkerton 1787, Birch 1846). Dr Campbell then argued that the magnificence of Scotland’s material culture from this period is proof to the contrary considering examples like the Book of Kells, high crosses of Iona or the Hunterston brooch. Unfortunately, the mainstream view in medieval art history tends to dismiss the decorative motifs on these as horror vacui. This is because the pinnacle of art of this period is defined by Carolingian Europe, for example, that of Charlemagne’s palace of Aachen which exhibits naturalistic art. In comparison to this standard, the abstract art in the material culture from, for example, the Dál Riatan royal capital of Dunadd is deemed inferior. However, Dr Campbell pointed out that continental art and architecture is a deliberate copy of Roman art; Carolingians even imported Roman craftspeople and material culture to build their palaces, trying to embody the Roman Empire in every way.

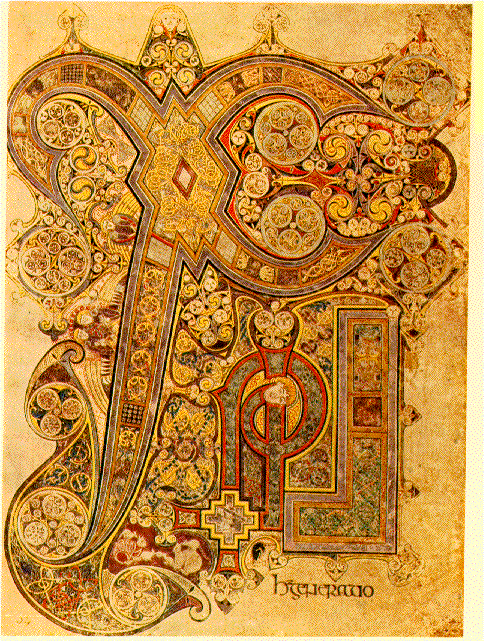

Instead of emulating the Romans, medieval Scotland is defined by insular creativity. The period bursts with rapid innovation. This is seen in the exponential change in stone monuments between the 7th to 8th century with changes in design, manufacture and conception; leaps in manuscript art with elaboration in decoration; transformations in metalwork from simple brooches in AD400 to the creation of the Hunterston brooch AD700; and new variations in crucible technology from one to many different forms. None of these local artistic and technological developments emulate Roman examples. The complexity of decorative abstract designs in figural scenes, manuscripts and sculpture, transformations in key patterns with spirals and interlace exhibit complexity of layout and geometric structure. This is exemplified in the image of St Matthew from the Book of Kells, which contains a whole series of complexities in colour and pattern. Medieval art in Scotland is highly innovative and creative, something that Carolingian is not, being derivative of Roman art.

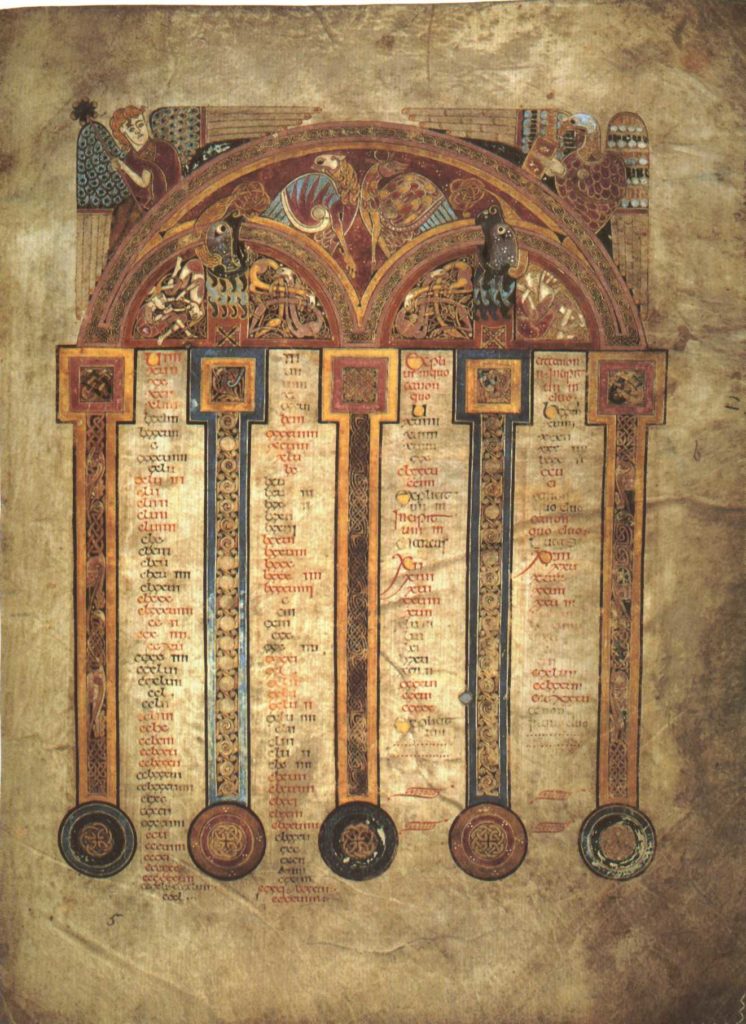

Dr Campbell credits this innovation to the introduction of writing. This new technology presented a new ordering of the world. This is reflected in, for example, the Book of Durrow canon tables that are establishing historical order. Additionally, rapid change may have been inspired by Scotland’s liminality and peripherality: an unstable environment of cultural change, which sparked innovation as an adaptive strategy.

In summary, Dr Campbell reflected on the early medieval Scotland as a period of intense creativity and openness to other cultures, which produced material culture and art with a mixture of cultural influences: Pictish, Germanic, Celtic and Mediterranean classical. This was a time of reordering the world with new technologies, which resulted in new art and writings that in return influenced the continent from the periphery, i.e. Adomnan’s writing were sought after and copied, art got exported and gradually incorporated into Carolingian art in various ways. Dr Campbell concluded by saying that communicating this is his goal, even though it remains difficult to persuade the continental mainstream on the importance of these points.