On 29 April 2014, the Centre welcomed Prof Stephen Driscoll (Director of the Centre) and Dr Ewan Campbell to discuss ‘How British is Scotland? Archaeological Origins of Scotland’. This continued the ongoing ‘How British is Scotland?’ series and follows Prof Bill Sweeney’s lecture. Below is this listener’s brief summary of the lecture.

Prof Driscoll began this two-part lecture with a discussion of the methodology of Scottish archaeology. The discipline of archaeology is the search for relics to help us better understand ourselves. This material culture is mute and therefore malleable, and as a result, it can be appropriated by political commentators to further their own ends. There is a general suspicion of ethnic labels in modern archaeology, now regarded as antiquated and artificial constructs subject to manipulation.

Attempting to identify early archaeological remains as ‘Scottish’ is fraught with difficulty, primarily due to geographical distribution and regional variation. Heavy silver chains found at Whitecleugh (and other areas in Britain) have been dubbed ‘Pictish’, yet similar artefacts have been found across Britain, and only three of the ten surviving chains were discovered in the accepted boundaries of the Pictish kingdom.

Similarly, Grooved ware pots were originally believed to be unique to Orkney but other examples have been found all over Britain, especially in Wessex. The extreme regional variation in Scotland is shown in the neolithic carved stone balls found in abundance in Aberdeenshire, but very scarce elsewhere. While Megalithic standing stones may be regarded as iconic examples of Scottish archaeology, they are found throughout Europe.

Round houses were a universal feature of early Britain, and they were open to adaptation based on the immediate environment, as shown by the ‘Scottish’ crannog. Prof Driscoll emphasised that houses are the most ‘highly expressive source of knowledge’ for archaeologists, and can attain global significance that transcends national boundaries, such as Skara Brae.

Literature can ‘package’ material in a concerted effort to express ‘Scottishness’, as shown by Allen and Anderson’s ‘The Early Christian Monuments of Scotland’ (1903). Prof Driscoll even suggested that even though Historic Scotland publications were valid educational tools, they also reinforced national boundaries and enhanced the ‘brand’ of Scotland. Perhaps in contrast, the National Museum of Scotland’s recent ‘Early People’ display adopted a ‘political detached’ approach, differing significantly from the medieval gallery on the floor above which overflows with patriotic imagery.

Continuing the lecture, Dr Ewan Campbell began with a discussion of the complex and varied origin myths of the Scottish nation which range from Ireland, Spain, Scythia and Norway. The shifting ethnicities were summed up in this glib statement in ‘1066 And All That’ by Sellar and Yeatman:

‘The Scots (originally Irish, but by now Scotch) were at this time inhabiting Ireland, having driven the Irish (Picts) out of Scotland; while the Picts (originally Scots) were now Irish (living in brackets) and vice versa. It is essential to keep these distinctions clearly in mind (and verce visa).’

In the Victorian period, a general consensus supporting the Irish origin emerged, yet Dr Campbell challenged this ‘Irish invasion’ when he found little archaeological evidence to support the theory. In 2001, he argued the sea was a linking mechanism and the true dividing line was the ‘Spine of Britain’. The public reaction to this new theory was fierce and Dr Campbell suggested a convincing psychological reason for this outcry. When toddlers are inevitably separated from their mothers or fathers they often latch onto a ‘transitional object’, like a teddy bear. Later in life, they attempt to ‘heal’ this separation through identification with an ‘abstract motherland’, and thus, when these ideas of origins are attacked it instils the ‘primal fear of abandonment’.

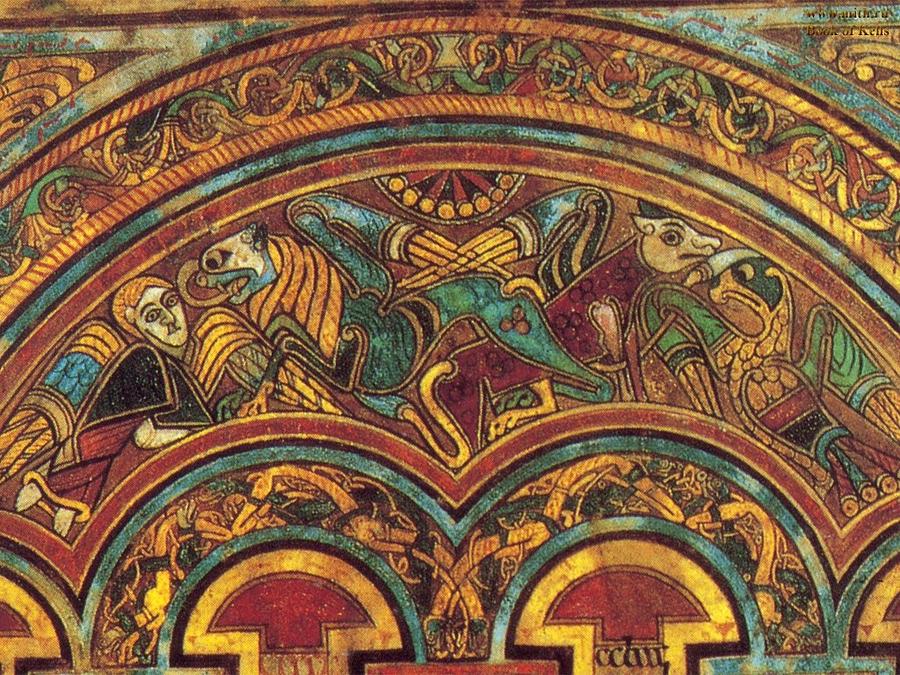

Since at least c.600, Scotland has been regarded as on the periphery of European civilisation. In c. 690, Adomnán described the British Isles as lying ‘at the remotest ends of the earth’. However, Dr Campbell argued that Scotland made several important contributions, including the Book of Kells, a fusion of German, Celtic, Pictish and Roman styles, insular art:

Iona was a hub of intellectual innovation, as evidenced by Adomnán’s output, and Scotland was also immersed in the mainstream of European culture through trade routes: pottery from sixth century Carthage has been found in Iona and an eastern Mediterranean amphora has been found in Rhynie.

Dr Campbell concluded by asserting that identity was fluid in this ‘Age of Migratory Ideas’, but Scotland was a ‘cultural powerhouse’ and only peripheral in a strict geographical sense.

Summary by Ross Crawford (PhD Researcher)

[…] was the penultimate lecture in the ‘How British is Scotland?’ series, and followed Professor Driscoll and Dr Campbell’s joint-lecture in April. Below is this listener’s brief summary of the […]

[…] How British is Scotland? Archaeological Origins of Scotland […]

The Book of Kells was done by Irish Monks at the Irish built monastary on Iona. The Irish invaded and controlled much of Scotland.

The jury is still out on the ‘Irish invasion’. See Dr Ewan Campbell’s theory, outlined briefly in this summary: http://cscs.academicblogs.co.uk/how-british-is-scotland-archaeological-origins-of-scotland/

My theory about the carved stone balls …

https://www.scribd.com/doc/251019947/The-Carved-Stone-Balls-of-Scotland

I would be very happy to be on your regular mailing list….congratulations and gratitude for this wonderful work and research that you provide….

My paper on the mysterious Carved Stone Balls of Scotland has caught the attention and interest of the Scottish Archaeological Research Framework (ScARF), the collaborative project funded by Historic Scotland and led by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. A PDF of the paper can be freely downloaded from the ScARF site at the following link …

http://www.scottishheritagehub.com/sites/default/files/u12/CarvedStoneBalls.pdf

My theory on the Carved Stone Balls of Scotland, linked in the previous comment, was recently covered by the The Herald and The Scotsman. Here is a link the Herald article … http://www.heraldscotland.com/news/16203657.Fresh_light_cast_on_the_mystery_of_Scotland_s_elaborately_carved_balls/

Would love to learn more about this. I’m an American with Scottish, English, Welsh and Irish Ancestors.

I also have French and Norman Ancestors. Then I found that my Irish may have been English etc.