On Tuesday 7 November 2017 the Centre welcomed back Dr Heather James of Calluna Archaeology, who offered us a fascinating glimpse at the preliminary findings of a recent community excavation at the site of All Hallows, Inchinnan in Renfrewshire, of which she was the lead archaeologist.

Titled ‘St Conval to All Hallows: Over 1400 Years and Counting’, this multi-strand community archaeology project is the first investigation which explores the significance of the site of the All Hallows church site over the past 1400 years from its origins in the early-Christian period, during the existence of the Kingdom of Strathclyde and into the modern period. It incorporates a multitude of disciplines, among them: geophysics, historical research, workshops, archaeology, model making, photogrammetry, Reflective Transformation Imaging (RTI), music and film making. The Inchinnan Historical Interest group provided the impetus for the excavation–coming off the back of a successful oral history project in 2014, titled ‘Inchinnan Farmlands To Erskine New Community’–and, after considering the possibilities, Dr James was eager to collaborate and offer her expertise.

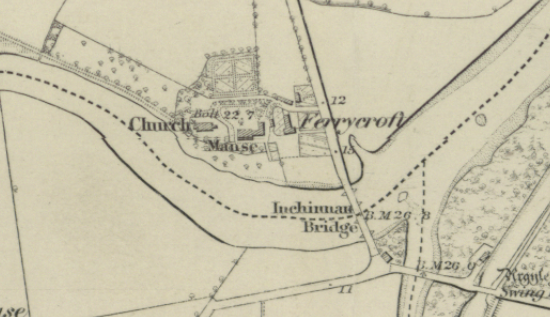

The site falls on the south-side of the Clyde between Glasgow and Paisley. It was the location of All Hallows parish church until the 1960s, when the kirk was knocked down to make way for the runway at Glasgow Airport. The site is believed to be the burial place of St. Conval, the 7th Century Irish saint and missionary who allegedly arrived there on a stone, which came loose and carried him across the Irish Sea. Furthermore, this was the location of several significant carved stones, such as those of the Govan ‘school’ of the Kingdom of Strathclyde and a group of medieval gravestones known locally as the ‘Templar’ stones.

The original church was built about 1100AD, around 20 years before Glasgow Cathedral. David I gifted the church to the Knights Templar in the 12th Century and, after the reformation, patronage passed to the Lennox Stewarts, then finally to the Campbells of Blythswood in 1737. In 1828 the medieval church was in a sorry state and, rather than risk restoration, it was demolished and a new, larger, rectangular kirk was built in its place. At the turn of the century, the church was considered too small to house its growing congregation and thus it was extended in 1904 and consecrated in dedication to All Hallows. Although the tower was removed, the building served the community until its demolition in the 60s. There are still upstanding remains of the 1904 church there today. Visit this webpage to have a look at a 3D digital reconstruction of the 20th century kirk, produced by Spectrum Heritage.

Dr James took us through the headaches of obtaining permission for such an ambitious project, from the Glasgow Airport Authority’s request for reassurance that geophysics equipment would not pull aeroplanes from the sky, to Renfrewshire council’s condition that human remains would not be dug up. Furthermore, while the original plan was to carry out the excavation over three sequential years, a primary funding body insisted that it be kept to one year initially. Dr James expressed her desire to continue with fieldwork in 2019.

Over the course of the excavation, which took place during a characteristically wet Paisley summer, the team faced a number of challenges (other than the dreich). First, they had to contend with thick deposits of concrete, clay and tarmac under the soil, presumably set down to level-out the landscape at an earlier date. Once the foundations of both the 1828 and 1904 churches were located, they had to deal with a substantial amount of debris, which came mostly from previous church demolitions but was intermixed with some potentially medieval material. Undeterred, however, the team persevered and unearthed a wealth of material, including a multitude of shards from stained- and painted-glass windows; 40 shards of medieval pottery; a 15th century Scottish Billon penny; several shroud pins; fragments from a (potentially) Iron-age bracelet; and a side-ways facing human skull, which, due to the council’s stipulation, soon prompted an end to the dig in that part of the trench.

The most striking element of the project is the level of community engagement. Dr James extolled the enthusiasm and effort of the local participants–including 40 adult volunteers, 5 schools and around 860 children–without whom the project would not have been possible. Aside from getting gey muckit during the hands-on excavation, the community were offered a menu of mud-free activities. This included an introduction to geophysics, seminars on the historical research behind the project (by our own Gilbert Márkus), and a visit to the Govan stones. Furthermore, free education packs are to be distributed among local schools.

Despite arriving at 3 University Gardens just off a flight from Australia, Dr Heather James–once a stalwart in the University’s Gregory building (archaeology)– was stimulating, and offered much food for thought over the course of the presentation. Perhaps the most profound and heart-warming consideration came towards the end. During the excavation, the team discovered the old porch-step which led up front of the church. This was where many in the community who are still alive today once posed for their wedding photographs after the ceremony. The location itself is still imbued with many fond memories. While archaeological projects generally aspire to unearth stories from the distant past, this one demonstrated the value of a history not so far from our own time.

Our next event on 14 November is the 4th instalment of the Centre’s Historical Conversations series. The Modern Panel will feature Prof. Callum Brown, Richard Finlay and W. Hamish Fraser, in conversation with our own Dr Catriona MacDonald. Tickets are currently sold out, but join the waiting list here. We Hope you will join us.

I love history, and enjoyed the article immensely.

Hi my family visited this site during an open day in 2018, it was a fantastic experience for all of us, especially my young boy ‘s, my eldest already wants to be an archaeologist. I spoke to a coup!e member’s of the inchinnan historical group at Erskine hospital’s motor bike meet yesterday and the lady there said that At Convals was not a Catholic church and the knights Templar were not Catholic. I have been fascinated by this for decades and read bits and pieces over they years, could you enlighten me to the religion practices in St Convals Inchinnan before the reformation? Thank you