On Tuesday, 26 September 2017 the Centre welcomed Gilbert Márkus (Glasgow) to discuss several themes behind his new book Conceiving a Nation. Prof Dauvit Broun highly recommended the book, stating that Márkus uses the entire range of textual material, including hagiography as literature and poetry, and places these materials in their archaeological context to create a bold new history of Scotland.

While it is often said that one should not judge a book by its cover, Gilbert addressed several themes from his book as they related to the cover of the book. The image comes from a detail in the Gospel of Luke in The Book of Kells, where the genealogy of Jesus is listed. While today genealogy is read as records of the reproductive behavior of someone’s ancestors, he argued that they should be read as literature. These genealogies were written to create a ‘usable past’ to persuade the reader of something in the present. In the New Testament of the Bible, there are two incompatible genealogies of Christ; in fact apart from a few key figures, there is not much overlap. These differences reflect the intended readership of the writers: Matthew was writing for a Jewish readership and, consequently, finishes with Abraham, the father of the people of Israel. Through Matthew’s genealogy, Jesus becomes the progenitor of the new Israel. Luke, on the other hand, was writing for a Gentile culture, and so traces the genealogy of Christ to Adam, the ancestor of everybody. Gilbert concluded that these genealogies were each constructed to make different theological point for their readership. Throughout his book, Gilbert treats the historical sources as a product of their writers: reading what the text says about the past tells us more about the writer’s agenda, his anticipated readership, and of what the writer is trying to persuade them.

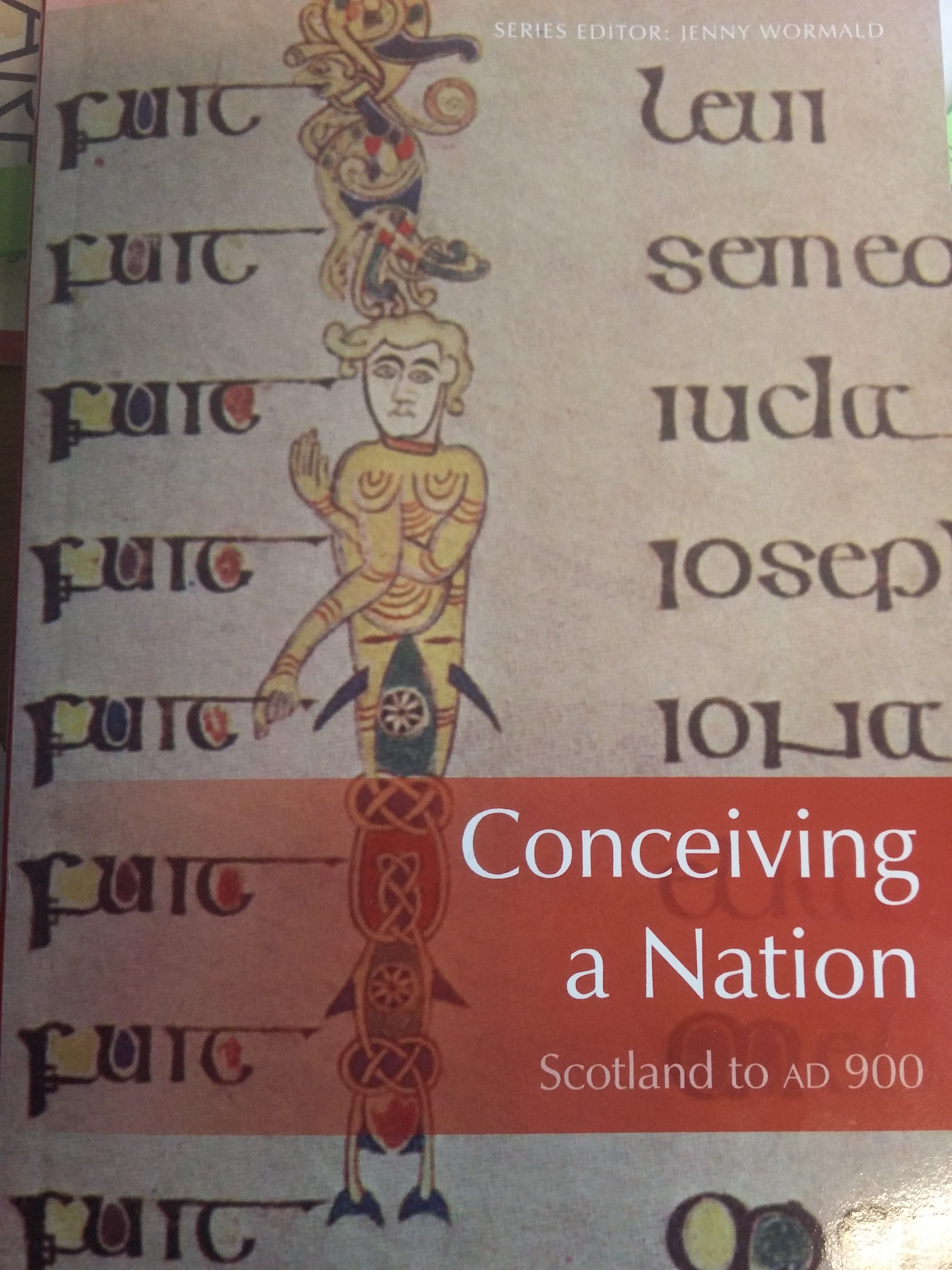

Returning to the cover, Gilbert described the featured figure: a figure with a great hat and no feet, with a strange fish tail. Some might interpret this as a merman, but Gilbert drew our attention to the fact that the figure is grabbing the “T” in Fuit with his right hand, and this fuit is attached to name “Jonah”. While there are technically two Jonahs in the Bible, one of which is Jesus’s ancestor and the other being the prophet that was swallowed by a great fish, in this telling of Jesus’s ancestors, they are one and the same. It does not matter that they are two different people, because they share the same name and these have their own persuasive power. In Adomnán’s Life of Columba, he uses names to demonstrate a connection between Jonah and St. Columba: the word “dove” is pronounced “Yonah” in Hebrew, as is Jonah’s name; in Greek, the word for dove is pronounced “peristera,” and in Latin it is called “Columba”. In Adomnán’s account, the two are the same: they are both prophets calling a kingdom to repentance. To connect their names even further, the bird that came down to land on Jesus when he was identified as the son of God was a dove, and Christ referred to doves as the symbol of innocence. Language has the power to create reality.

In addition to the associations created through language and the power of names, the picture of Jonah creates further connections with Christ; his arms are crossed in the shape of the Greek letter “X,” the first letter of Christos, which is a constantly recurring motif in the Book of Kells. His body is also coloured gold, which is often used in medieval art to reflect divinity due to its eternal changelessness and beauty. Gilbert emphasized that there is a playful engagement with image and text throughout these books that play with these changes of associations. In order to get at these associations in genealogy, Gilbert stated that it was necessary to immerse oneself in the sources.

Márkus also sought to address the Ethnic Fallacy which pervades the study of the early medieval period. He said that this was one aspect of Alfred Smyth’s Warlords and Holy Men (1984) that he was dissatisfied with: the sense of strictly defined ethnic groups in direct opposition with each other, whether it was the Celts vs the Romans, or the Picts vs the Gaels. Human reality is much more complicated than that. In many of the historical sources we have from this period, people create ethnicity by reciting genealogies, by telling stories about their ancestors to create these pasts, to create a sense of ethnic cohesion and a sense of difference from others. However, we have many archaeological artefacts from this period which suggest that an individual’s sense of their ethnic identity is never so clear cut as that. In the case of the Latinus stone, the earliest Christian stone memorial from Scotland, the individual erecting the stone claims his descent from a British father, but professes Roman sentiments. Gilbert argued that the early medieval period is a “slurry of ethnic wash and fluidity” that we should celebrate.

Finally, genealogy was a tool used to legitimate power in this period. While almost all texts from the early medieval period reflect power relations, genealogies were often used to connect individuals to powerful figures of the past to legitimate their claim. Genealogies of the saints were always written and rewritten, likely so that people who claim to have those saints in their ancestry could have authority over the church.

Márkus concluded by stating that in order to better understand the past, a sympathetic reading of the lives of the past is required. While the past is, in a way, another country, that doesn’t mean it is unintelligible to us.

If you are interested in purchasing a copy of Gilbert’s book, it is available through the Edinburgh University Press, here.

Summary by Megan Kasten (PhD Researcher)

Our next seminar will be the Medieval Panel in our Historical Conversations series, featuring Prof Steve Boardman (University of Edinburgh); Prof Dauvit Broun (University of Glasgow); and Prof Stephen Driscoll (University of Glasgow. This session will be chaired by Prof Thomas Clancy (University of Glasgow). This will be held on 10 October 2017 in the Kelvin Hall Lecture Theatre. All welcome, but please register for the event via Eventbrite, here.