On the evening of Tuesday 11th December 2018, the Centre was delighted to welcome two of our very own, Dr Stephen Mullen and Dr Andrew MacKillop, who concluded this year’s seminar series with a fascinating tag-team discussion of two very different ‘Scottish’ islands: St Kilda and Tobago. Our usual venue in 3 University Gardens was packed out the door as Dr Martin MacGregor got proceedings underway by introducing our speakers. Between 2015 and 2017, Dr Mullen worked as a postdoctoral research assistant in History on the Leverhulme funded project ‘Runaway Slaves in Britain: Bondage, Race and Freedom in the Eighteenth Century’. He is currently lecturing at the university, and putting the finishing touches on his monograph, which illuminates Glasgow’s role in plantation, slavery and empire in the 18th and 19th centuries. Dr Mackillop completed his PhD at the University of Glasgow in 1995, on military recruitment in the Highlands, 1739-1815. A recent acquisition from the University of Aberdeen, he now works at Glasgow as a senior lecturer in Scottish History. His research is primarily concerned with the role of Scots in the British Empire.

Dr Mullen kicked off by discussing the influence of Scots in Tobago in the 18th and 19th centuries. Tobago is a small Caribbean island located about 100 miles off the east coast of Venezuela, and about 20 miles northeast of mainland Trinidad. Under French control up until 1763, the island was used to cultivate a variety of crops, particularly cotton, sugar and indigo. However, when the Seven Years’ War concluded with a French defeat, the island was subsumed into the British Empire. Soon thereafter, as the British presence and extent of slavery increased, cotton production was phased out in favour of large-scale cultivation of sugar cane. In 1776, Lachlan Campbell, the Deputy Provost Marshall of Tobago, observed that the greatest part of the island’s planters were of Scots origin – going so far as to refer to it as a ‘Scotch colony’. This was what Devine would term ‘empire by stealth’: while Scotland did not formally possess Tobago, through their presence, Scots managed to dominate economic life in the colony. Taking this as his starting point, Dr Mullen set out to answer two key questions. First, how important were Scots to Tobago? And, second, how important was Tobago to Scotland?

Lachlan Campbell’s observation was substantiated further when Sir William Young, recently appointed governor of Tobago, produced a statistical account of the colony. While the enquiry was carried out largely in response to concerns about a possible slave uprising, the estate and militia lists it contained reveal the extent of Scottish influence. At the time of the report Scotland contained only 14% of the British population, yet, in Tobago, Scots constituted over half of the resident planter population. Moreover, Scots were not simply visiting Tobago, extracting wealth, then returning to their homeland, as much of the established scholarship suggests. Indeed, many remained in Tobago for 10 or more years in order to gain land. They also constituted the bulk of the supervisory class in the colony. Scottish physician, Dr James McTear, who travelled to Tobago in 1820, observed that the majority of estates were owned by Scots. Dr Mullen concluded by pointing out that William Young’s enquiry provides a starting point for tracing the wealth extracted from Tobago back to Scotland, before handing over to Dr MacKillop.

Dr MacKillop’s contribution was about St Kilda, a Scottish place that was, in very different but equally significant respects, as imperial a space as Tobago. He began by making the distinction between a ‘place’—i.e. a geographical location—and a ‘space’, which brings together the cultural, economic, social and aesthetic aspects that might be projected onto a place by outside agents. St Kilda is an archipelago of small islands about 45 miles west of the Hebrides. Most of the scholarly attention it has received deals with the disruptive impact of modernity, imperialism, and social and economic change on island life. However, Dr Mackillop sought instead to explore the island’s substantial and sustained links to British imperialism. Between 1778 and 1871, Hiorta, the largest inhabited island in the archipelago, was owned by four proprietors, each with direct experience of colonialism in India and maritime trade with Asia. As Mackillop points out, this meant that for 93 of the last 200 years of Hiorta’s existence as a living community, the island’s development, as both a place and an imagined space, was unavoidably shaped by imperialism.

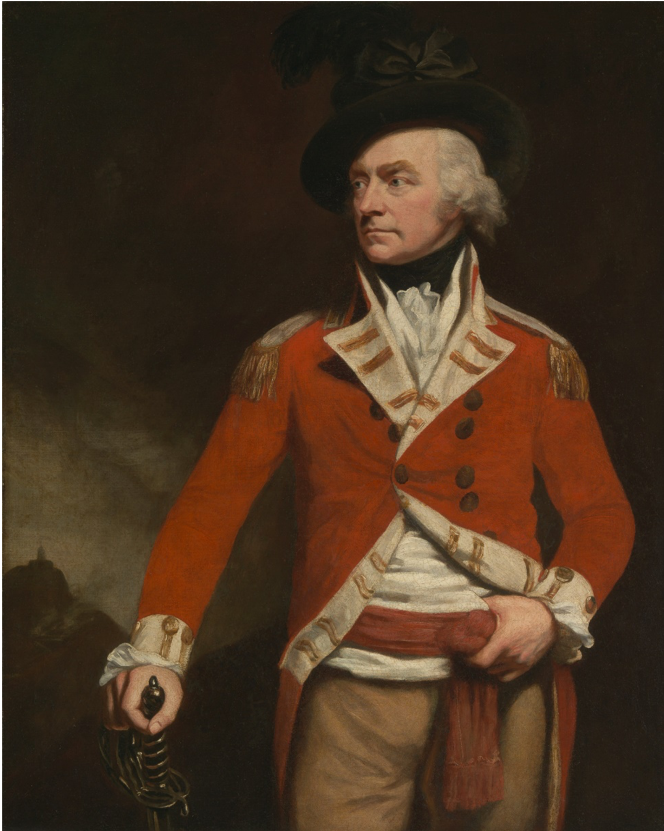

Departing from earlier treatments, which emphasise the administrative changes to estate management occasioned by changes in the island’s ownership, Dr Mackillop instead explored the cultural priorities of those who brought about these changes. The first proprietor discussed by Mackillop was Alexander MacLeod-Hume of Harris, a civil servant to the East India Company. In 1804, he sold the island for £1,350 to Colonel Donald MacLeod, a retired Madras army officer. Despite making his fortune in Asia, Col. MacLeod had a direct family connection to the island. His father, Alexander MacLeod, was an SSPCK-sponsored missionary in Hiorta from 1743, meaning that Col. MacLeod would have spent much of his childhood and young adulthood on the island before joining the Madras army in 1767. Therefore, this acquisition was imbued with personal meaning for Col. MacLeod, demonstrated by him changing his title to ‘Col. MacLeod of St Kilda’ immediately after purchasing the estate.

MacKillop also demonstrated the ways in which his imperial experience influenced his stint as landlord. By the time of the acquisition, those who had acquired lands with imperial profits had begun to attract the odium of commentators. Such individuals were generally portrayed as excessive social-climbers, authoritarian, and unfeeling towards their tenantry. In a candid letter to his kinsman in Madras in 1798, Donald explained the low regard for returning imperial officers that prevailed:

Here the opinion universally attached still to a person who returns with any fortune from India is grievous indeed, we are ever considered as worse that heathens.

From Donald’s point of view, the acquisition of St Kilda was an effective antidote to what Mackillop described as ‘the taint of the Eastern adventurer’, the stereotypical social-climber. What better way to rehabilitate one’s reputation, and join the ranks of respectable landed society, than to highlight your longstanding family connection to a place so widely regarded as both authentically natural and distinctively Scottish? In his capacity as landlord, Col. MacLeod championed the people of St Kilda. In an article published in The Scots Magazine shortly before his death in 1814, MacLeod extolled the economic value of the island and its people, and their contribution to the British state. As Mackillop pointed out, this was not pure sentimentalism on MacLeod’s part. Indeed, he had willingly evicted the tenantry on his Lochfyneside estate at an earlier date. Rather, his administration of St Kilda was seen as a means of redefining perceptions of the landlord. It is revealing that, in his his first act as owner, MacLeod took direct control of the estate, removing the tacksman, William MacNeil, who was seen to have wielded excessive power to raise rents. This could be considered atypical of an improving landlord. However, given the criticism that had been levelled at MacLeod’s predecessors, this may reflect the influence of the island’s inhabitants in affecting the ethos of the new regime. Moreover, MacLeod and his successors would allow greater rent arrears on the islands than in their Argyll lands. In this respect, it could be argued that the landlord no longer improved the land; rather, it was the land that improved the landlord.

MacKillop concluded by pointing out that his examples reveal the far-reaching influence of empire in Scotland. No part of the country was free from its impact. Indeed, in the imperial era, St Kilda remained what it always had been: not an isolated island, removed from developments elsewhere, as it was portrayed by countless commentators, but an island that was still strikingly connected to the world it inhabited.

Thanks to everyone who joined us on Tuesday evening for the seminar and the Christmas party that followed. The seminar series returns on Tuesday 8th January, when Tomás Carraigáin joins us to discuss the royal and monastic islands of Early Medieval Corcu Duibne. We hope you will join us, but, in the meantime, a very Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to everyone.