On the 1st of October 2019 Dr Simon Taylor (best known for his pioneering work on the place-names of Fife and, most recently, Kinross-shire) continued the Centre’s unofficial mini-series of travel presentations by delivering a captivating talk on his 2017 expedition across the ‘Spine of Britain, from Dunkeld to Iona.

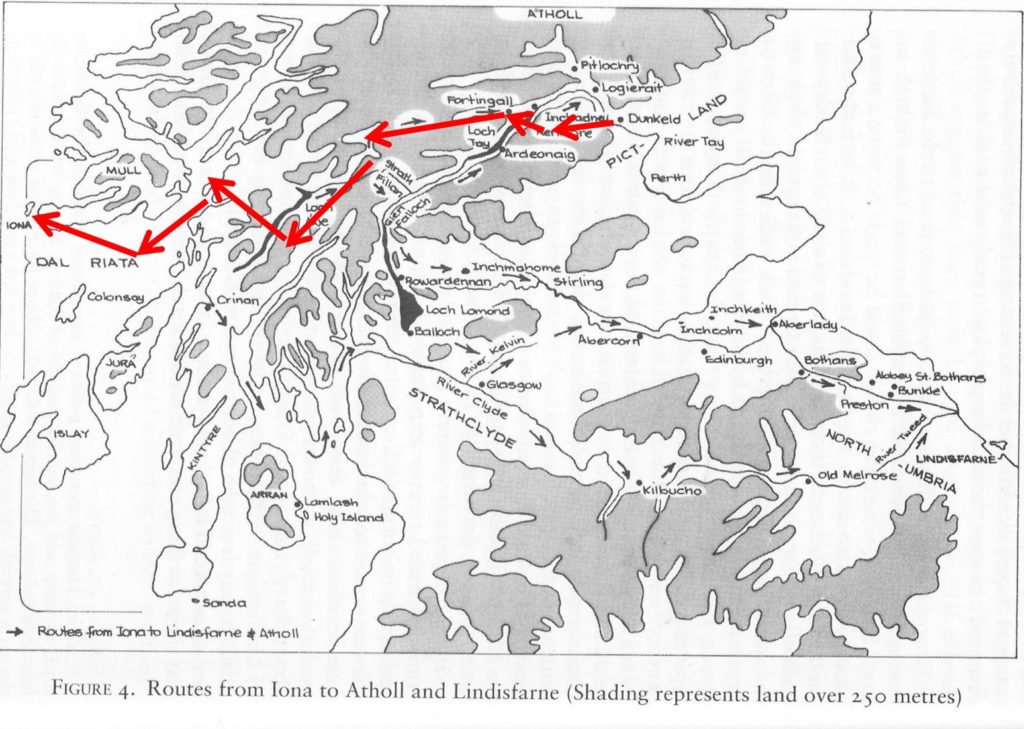

Explaining that the idea for the walk came from a conversation (in the pub – where good ideas often originate!) between himself and Dr Pamela O’Neil from the University of Sydney in 2012; Dr Taylor elaborated that the year 2017 had been chosen as it was the 1,300th anniversary of the expulsion by the Pictish King Nechtan (Naitan) of the family of Iona ‘across the spine of Britain’ which occurred in 717 (Annals of Ulster: Expulsio familie Ie trans Dorsum Brittanie a Necto rege). Dunkeld was chosen as the starting point for the expedition as it is on the southern edge of Atholl and was, at the time of the expulsion, a Pictish sub-kingdom – there is toponymic and dedicatory evidence which points to strong links between Atholl and Iona in the late 7th and early 8th century. Dunkeld retained its importance in the early Christian landscape of Scotland and became the centre of the cult of Columba in eastern Scotland following Cinead mac Alpín’s transportation of relics of Columba to the church there around 850. The walk took place over 16 days between the 23rd of August and the 7th of September – dates selected to acknowledge the importance of Adomnán in the whole enterprise, while still factoring in the Scottish weather. Adomnán’s main feast-day is the 23rd September, however it was felt that this was a little late to be arriving on Iona and so instead the walk culminated on his subsidiary feast-day (as celebrated at his foundation of Raphoe, Co. Donegal) with the hopes that this would mean more favourable weather conditions. Dr Taylor began by reflecting on last week’s discussion of phenomenology, noting that they had taken a phenomenological approach to the 2017 walk perhaps without being entirely conscious of it. The walk allowed them to experience the landscape in the present while also trying to access it, as historians, in the past. Dr Taylor noted that he was just as much interested in the spaces in-between along the route, as much as the places themselves, and that the walk was a way to weave together a thread that joins together things that seem unconnected on distribution maps.

Dr Taylor took us through a whistle-stop tour of the walking route, highlighting particular points of interest along the way, many of them early ecclesiastical sites. An early discovery for the walkers was that many of the most likely medieval routes are still in use today and are now busy A roads and B roads with no provision for walkers – meaning that often a slightly alternative route was necessary for safety reasons. On the first day of the walk they passed through the medieval parish of Lagganally, where there was a medieval parish kirk; the first element of this place-name is the recently identified Old Gaelic loc, a loan-word from Latin locus ‘a place’, especially ‘a special/holy place’. Day 3 of the journey took the walkers through the Appin of Dull, the name of which is an Adomnán dedication and Dr Taylor explained that this was a large and important territory and parish when it is first mentioned c.1170, and that the parish could possibly have belonged to Iona. Also on Day 3 they visited Fortingall, which is an early place name containing as its second element Gaelic cill – a church – suggesting an early ecclesiastical presence in the area (c.700-c.800). At Fortingall the group saw some high quality medieval carved stones, as well as the Bell of Fortingall, which was tragically stolen about 10 days later. The walk continued through Glen Lyon and past the Cladh Bhranno burial ground, which has been the location of some recent archaeological investigations by Dr Anouk Busset and Dr Adrian Maldonado of the University of Glasgow. The walkers set up camp overnight between Days 6 and 7 in Pubil and Dr Taylor noted that this place-name originates from the Old Gaelic, pupall (Gaelic, pùball ) meaning ‘tent’. However, this place-name element could also have religious connotations (as in Pubble, formerly Puball Pátraic in Co. Fermanagh, where St Patrick pitched his text), and suggests the possibility of people travelling and talking their liturgical space with them along the way. The group continued around Beinn Mhanach (‘monks’ hill’), passing through Gleann Cailliche (‘glen of the old woman’).

On Day 11 the walkers were afforded a bit of a rest as they took a boat across Loch Awe and a short detour to Inishail, an island in the Loch with a medieval parish kirk and a collection of carved stones, both early and late medieval – also the burial place of the dukes of Argyll. Dr Taylor asserted that medieval people would absolutely have made use of travelling over water where it was possible, and that the several place names around the Loch containing the place-name element port testify to there having been several harbours there, likely with ferries running across the water. On the other side of Loch Awe the group walked through Kilchrenan (‘church of the deacon’ – Old Gaelic, dechon), which is possibly the earliest recorded cill—name in Scotland and is mentioned in Adomnán’s Life of Columba. Reaching Oban by the end of Day 13 the group travelled onwards to Iona via Eileach an Naoimh, Ardalanish and Fionnphort. Dr Taylor ended his discussion by summarising some things that he had become more aware of during this phenomenological approach to the journey across the ‘spine of Britain’; the importance of networks of support; the high degree of organisation and resources required for efficient travel overland; the cumulative exhaustion of many days travelling and the need for rest and sustenance along the way; the way that travelling through the landscape on foot allows the landscape to unfold slowly enough that the traveller is aware of subtle changes, and the way that this allows the traveller to see the landscape through different eyes, putting out modern roadworks into perspective as well as making sense of place-names along a route which today seems to go nowhere.

Myra Booth-Cockcroft.

Can someone point me towards the recent research on Old Gaelic ‘loc’ placenames mentioned here? Thanks!