On 18 February 2014, the Centre was delighted to welcome Dr Gillian Kenny (Trinity College Dublin) to discuss ‘The “Mammy” Effect – Tracing cultural exchange through intermarriage in later medieval Ireland’. Below is this listener’s brief summary of the lecture.

Dr Kenny’s presentation was an extension of her work on Anglo-Irish and Gaelic women in medieval Ireland, a topic on which she has written extensively, including a published book. She explained that the eponymous ‘Mammy’ was traditionally the foster-mother, not the birth-mother. The ‘Mammy’ was the nexus of bonds of affection and loyalty, often enjoying stronger emotional ties with the children than even the birth-mother. Dr Kenny placed the ‘Mammy’, and other contemporary women, within a context of social and cultural exchange between the Anglo-Irish and the Gaelic Irish.

From the viewpoint of the Anglo-Irish administration in Dublin, cultural exchange with the Gaelic Irish was not to be tolerated, as shown in the Statutes of Kilkenny of 1366. Fearful of the perceived degeneracy of the native people, the Statutes forbade intermarriage between Gaelic Irish and English, and the fosterage of Irish children by the English. This contradicted the norms of the time which had seen increasing inter-marriage between the two cultural groups. This was especially prevalent in the early days of the ‘incomplete conquest’ by the Anglo-Normans. Often the invaders were completely surrounded by hostile Gaelic neighbours. Therefore, inter-marriage was a political necessity and a survival tactic, the assumption being it was harder to attack your enemy if you were related to them!

Increasing Gaelicisation was found in the West of Ireland, with many Anglo-Norman settlers quickly adapting and identifying with Gaelic cultural practice. Some families had no qualms whatsoever about abandoning their old Anglo-Norman ways. Most notable perhaps were the Costello family, descended from an Anglo-Norman knight called Jocelyn de Angulo, who essentially became Irish chieftains within fifty years of their settlement. Interestingly however, they maintained their English Christian names, e.g. Thomas.

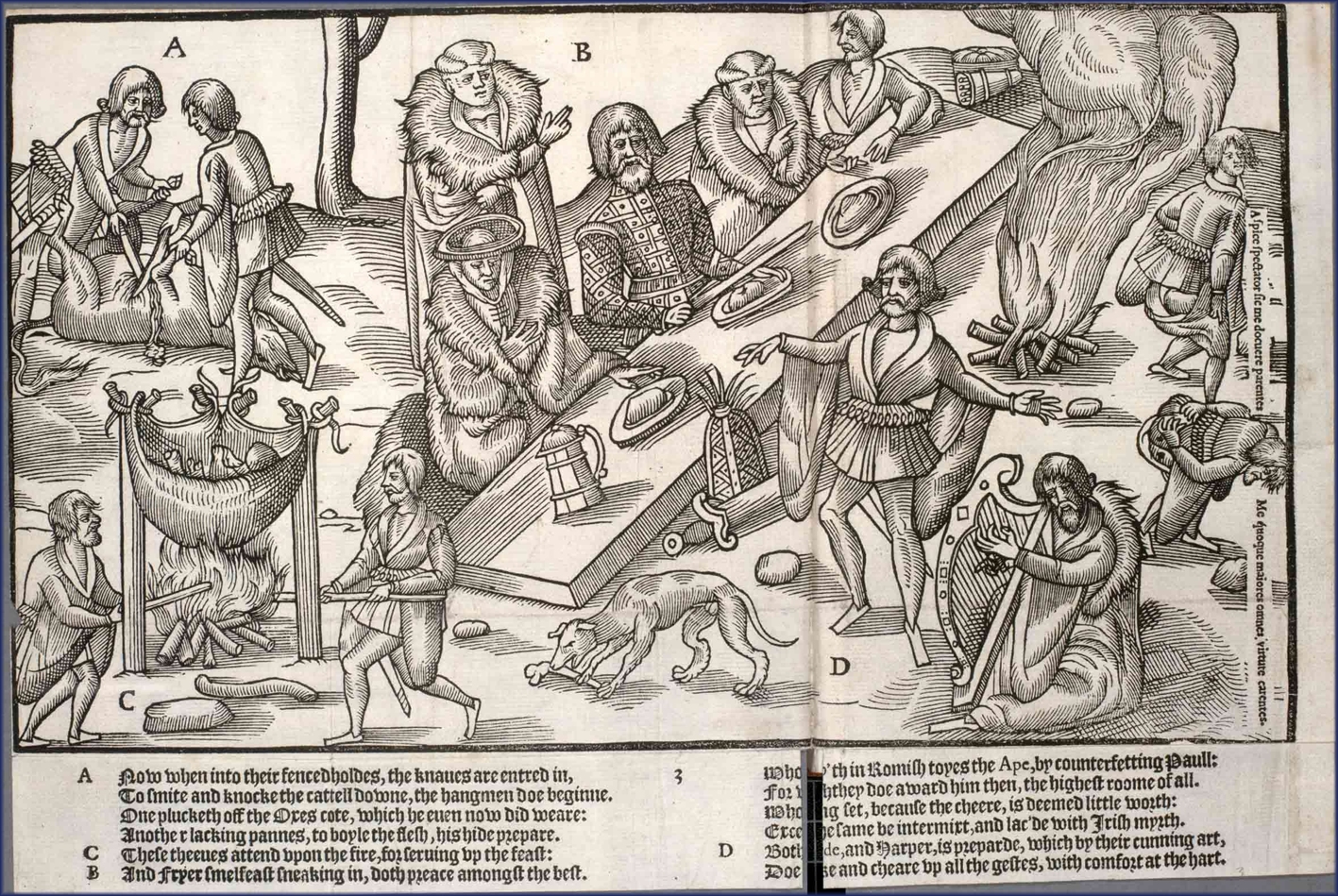

Gaelic Irish lords coveted the extension of English Common law, as it brought privileges like dower rights. If a Gaelic Irish woman married an Anglo-Norman man, his family were not required to provide a dower. Calls for an extension of dower rights even made its way into the 1317 Remonstrance of Princes – clearly it was an ongoing issue. Yet Gaelic Irish women generally had more rights than their Anglo-Irish counterparts as they were not wholly subject to their husbands. They had freedom of action, extending to independent patronage of bards, or even leading mercenaries on raiding expeditions. Furthermore, many Gaelic Irish women were heavily embroiled in the political machinations of medieval society.

Fosterage was a social practice intended to strengthen ties between families. Social superiors would foster the male child (around the age of seven) of a lesser family. In comparison to Scotland, there is little surviving evidence of fosterage in Ireland, yet it is clear that a foster-mother was afforded high social status. In this respect they commanded an esteem similar to that of a concubine. Many Anglo-Irish lords ‘took what they liked’ from Irish law, and predictably perhaps, this typically included concubinage. In Irish law, little distinction was made in inheritance between children begotten of legitimate marriage or concubinage, which could cause tension with the stricter rules in Common law. As a result, succession struggles were frequent. Dr Kenny noted that the high status position of concubines was simply ‘incomprehensible’ to the Anglo-Irish, as there was no equivalent in their culture.

The adoption of certain Gaelic customs without full Gaelicisation led to the emergence of a ‘middle nation’. Determined Anglo-Irish, based primarily in the east of the country, regarded this behaviour as ‘shocking’, and a lapse into savagery. Some Anglo-Irish families maintained a firm English identity despite constant interaction with the Gaelic Irish through intermarriage and fosterage. The Butlers of Ormond are a key example of continuous affiliation with English culture, as are the FitzMaurice earls of Kerry. Dr Kenny concluded by highlighting that these interactions must have raised questions of identity, especially for the children of intermarriage and fosterage. These questions are ripe for further investigation.

Summary by Ross Crawford (PhD Researcher)

Our seminar series continues next week, 25 February, with Prof Dauvit Broun, ‘How British is Scotland? Britain and Scottish Independence in the Middle Ages’. This will be held in the Western Infirmary Lecture Theatre at 5.30pm. All welcome.