On 25 November 2014, the Centre was delighted to welcome Dr Alan MacNiven (University of Edinburgh) to discuss ‘What’s in a Name? Norse Naming Strategies in the Hebrides’. This seminar was held in conjunction with Onomastication, the onomastics reading group. Below is this listener’s brief summary of the lecture.

On 2 July 1266, the envoys of King Magnus III met with King Alexander III to finalize the peace between Scotland and Norway, following the misadventure of Magnus’ father, Hakon, at Largs three years earlier. The Norwegians agreed to concede forever their claim to the islands of Scotland and both sides remitted all depredations committed by either party. Bad relations between the two nations had been the norm for centuries. In the outer isles of Scotland, there was violent displacement of the native population, but it is generally thought the Inner Hebrides escaped this fate. There is no documentary evidence of Norwegian raids on Islay, for example, despite the fact they must have passed ‘within shouting distance’ of the island when raiding Rathlin or Iona. Between 740-1095 there is a ‘blind spot’ in the historical record for Islay (and indeed all of Argyll) which corresponds neatly with the Viking Age. The archaeological record for Islay has evidence of high-status Scandinavian objects, found primarily in arable land, suggesting a settled pagan elite.

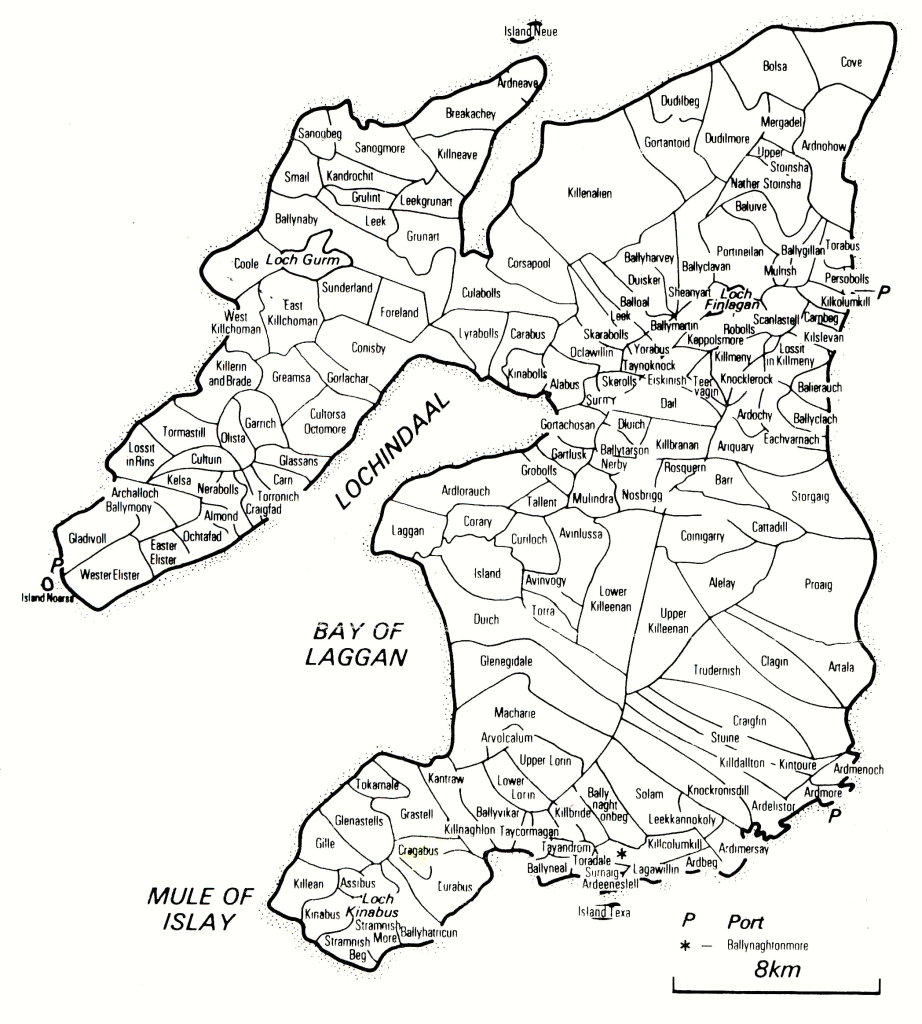

It was thought that of the c. 6000 place names on Islay, two-thirds were Scots or English (such as Port Ellen and Port Charlotte) and one-third were Gaelic. However, many of these Gaelic names are ‘romantic’ and make little etymological sense, such as Beinn Tart a’ Mhill (Hill of the Thirsty Hill). However, this example (and many others) can be reasonably explained by Norse derivation, i.e. Beinn Hartafjall (Stag Hill). In 1772, Thomas Pennant argued that Islay had more Norse (‘Danish’) names than any other island, but while this is a ‘massive exaggeration’, Norse names may make up one-fifth of Islay’s toponyms. The distribution of Norse names covers the full extent of the island, both inland and coastal.

Some of these names may have been borrowed from existing local Gaelic names with some adjustments, also called ‘lexical substitution’. To illustrate this idea, Dr MacNiven presented a picture of a nail in a jar and asked the audience to ‘say what they see’, revealing the genuine Hebridean place name, ‘Na h-Eileanan an Iar’ (Western Isles)! Some of the Norse names may also have been genuinely new and original, which would suggest an elevated social standing for the Norse settlers. However, this is very difficult to determine with absolute certainty as many of the names may have been adaptations of pre-existing Gaelic names, or incorporated loan words from Norse.

Apart from the name of the island itself, there are no surviving Gaelic place names that existed before the Viking Age. Words like ‘baile’ or ‘cill’ are pre-Norse but only became common in the late middle ages. This suggests a sharp break in continuity and ultimately, a Norse invasion of the island. There must have been some acceptance of the Norse occupation or presence on Islay as so many Norse place names have survived to the present day. Eventually the Norse settlers (or invaders) came to speak Gaelic themselves and this transitional period allowed the language to creep back into the island.

Summary by Ross Crawford

Our series continues next Tuesday 2 December with Dr Aonghas MacCoinnich, ‘Plantation in the Hebrides: the Dutch in Stornoway, 1628-31’. This continues the ‘Scotland and Europe’ series and will be held in Room 202, 3 University Gardens at 5.30pm. All welcome.