On the evening of Tuesday 6th November, the Centre was delighted to welcome Dr Simon Egan, who continued our Islands theme with a stimulating introduction to his current research project, which investigates the role played by the ‘Gaelic world’ in the wider political theatre of the Atlantic Archipelago (aka the British Isles) from the 15th to the 17th Centuries. A recent arrival at the University of Glasgow as a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Dr Egan completed his PhD at University College Cork in 2016 on the resurgence of Gaelic power in Ireland and Scotland in the later Middle Ages. He then undertook a year of postdoctoral research, funded by the Society of Renaissance Studies. With his latest project, Dr Egan aims to produce a comprehensive narrative history of politics in the Gaelic-speaking world c. 1400–c.1603, with a particular focus on how this impinged upon developments in the nascent ‘British’ state.

Dr Egan began with a health-warning. The terms ‘Gaelic world’ and Gaeltacht, he points outs, have been adopted by many scholars, such as Prof. Steven G. Ellis, to portray the Gaelic-speaking regions of Ireland and Scotland as a unified cultural (and, potentially, political) entity in the late-medieval and early modern periods. Such a conception, however, has been cast into question recently by several scholars, among them Drs Wilson McLeod, Martin MacGregor and Aonghas MacCoinnich. While not discounting the conceptual utility of a ‘Gaelic world’ entirely, Egan is much more circumspect in how he seeks to define such a concept. As he demonstrates in his doctoral thesis, there are certainly parallels to be drawn between the experiences of Gaelic Scotland and Ireland through the 14th, and into the 15th centuries; the cooling of climates and the impact of the Black Death led to the withering of crown authority in both countries, followed by a resurgence of Gaelic influence. In Ireland, this was typified by the steady ‘Gaelicisation’ of English settlers, and their disengagement with colonial politics. Moreover, in Scotland, Robert the Bruce’s wars saw the decline of Anglo-Norman lordship in the northwest, leaving a power vacuum that came to be filled by the MacDonald Lordship of the Isles.

The nuance of Egan’s approach to the ‘Gaelic world’ is best illustrated by his ability to place developments in Gaelic Scotland and Ireland within the context of, and in parallel to, the processes of English and Scottish ‘state formation’. While there is a tendency to view the Scottish and English crowns as diametrically opposed to the existence of a ‘Gaelic world’, Egan points out that, prior to the Reformation at least, Gaelic lords often served as crucial political allies. Just as the Scottish crown could exploit alliances in Ireland to cause trouble for the English lordship, the English crown could rely on Lordship of the Isles to destabilise the Scottish kingdom.

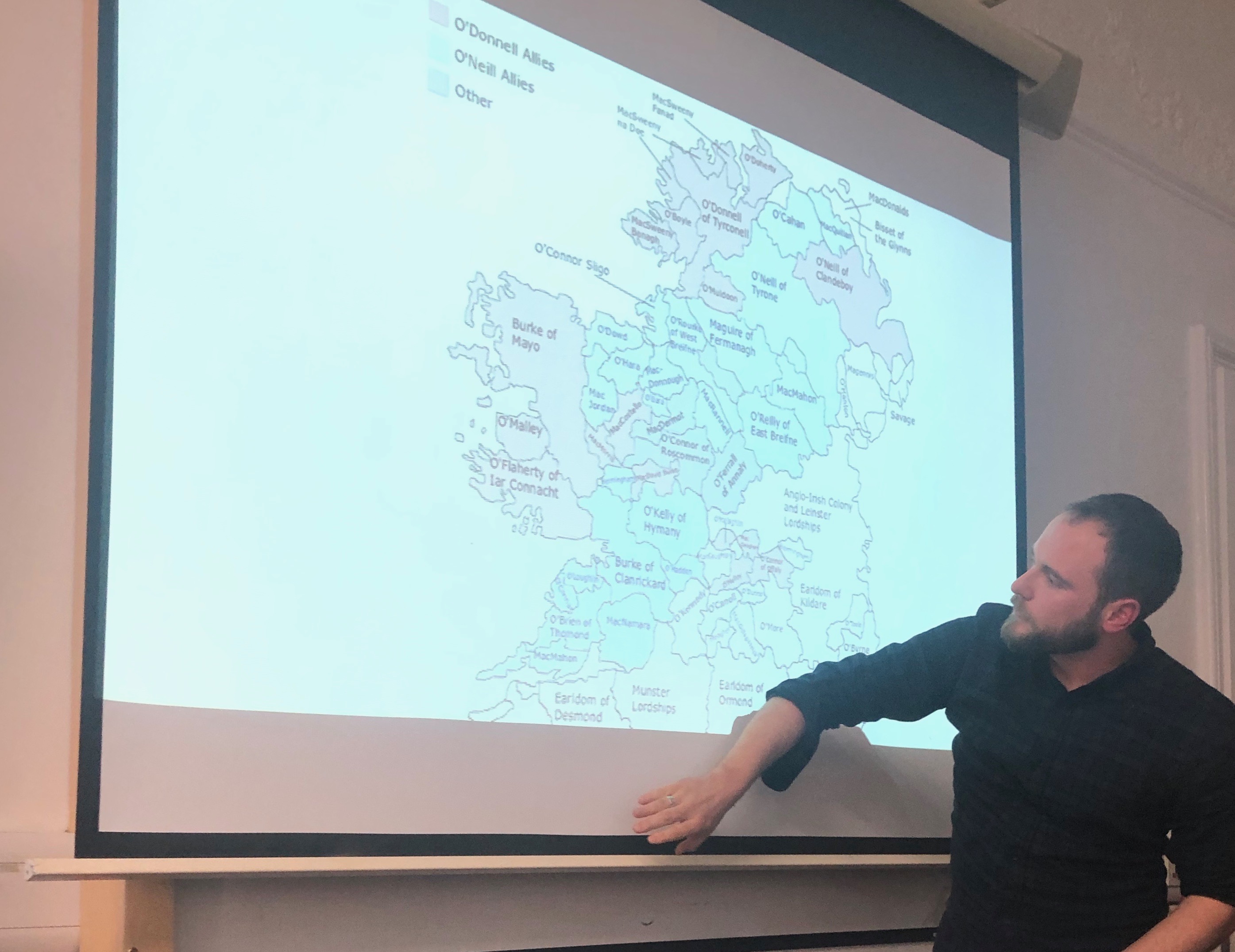

Dr Egan, however, seeks also to understand the motivations and responses of the Gaelic lords themselves. The two most influential Gaelic lordships, the O’Donnells of Tyrconnell and the O’Neills of Tyrone, were deeply involved with the dynastic politics of the period. The O’Donnells, for example, played an indirect role in the ill-fated Flodden campaign in 1513 in support of the Scottish crown. While we can be certain that this alliance survived the battle’s conclusion, we have yet to establish the role of the O’Donnells in the recovery of the Scottish kingdom post-Flodden. Furthermore, following the Henry VIII’s reformation in England, beginning with the intrigue of James V of Scotland in the island, Ireland became increasingly recognised as a potential platform for continental powers to destabilise the English crown.

Egan drew his presentation to a close by discussing the implications of the Treaty of Berwick of 1560. The result of negotiations between the court of Elizabeth I and the group of Scottish nobles knows as the ‘Lords of the Congregation’, the treaty marked a formal end to Anglo-Scottish enmity. Of course, James VI would continue to utilise the Highland mercenary trade in Ireland ’to ladder the Queen of England’s tights’, as Allan Macinnes so colourfully puts it, up until his accession to the English throne in 1603. Nevertheless, this shift in Anglo-Scottish relations towards a closer rapprochement, based largely on a shared Protestantism, had an undeniably significant impact on the Gaelic world. A key question, which Dr Egan seeks to answer is: how did the Irish lords react to this new environment? We look forward to hearing more about Dr Simon Egan’s project in due course.

Many thanks to all who made it out for last night’s seminar. At our next event on Tuesday 13th November, we will host Dr Stuart Jeffrey (Glasgow School of Art) and Prof. Sian Jones (University of Stirling), who will be discussing findings from recent excavations on Staffa. We hope you will join us.