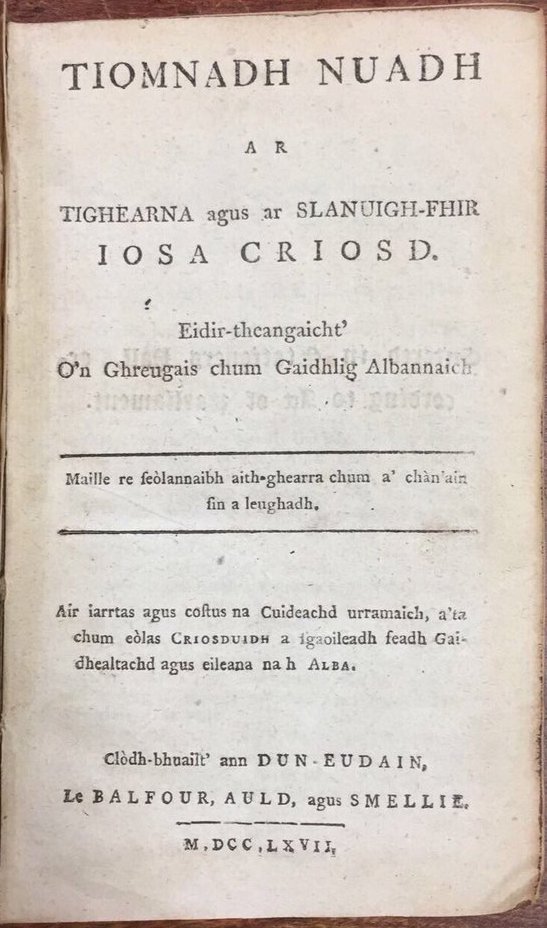

On Tuesday 28 November, the Centre was delighted to welcome Ronald Black, one of the most distinguished scholars of Gaelic literature and culture, to deliver the 12th Annual Angus Matheson Lecture. This year marks the 61st anniversary of the appointment of Angus Matheson as first Chair of Celtic at the University, a post he would hold from 1956 to 1962. However, 2017 also marks the twin anniversaries of the publication of two landmark Gaelic texts: John Carswell’s Foirm na n-Urrnuidheadh (1567), the first book ever printed in Gaelic, and the Gaelic New Testament (1767). The former was a translation-cum-adaptation of John Knox’s Book of Common Order; the latter, the first published translation of the Bible into the Scottish Gaelic vernacular. It was very appropriate, then, that Ronald Black chose to discuss the ways in which the Reformation changed the Gaelic world.

Ronald began by taking us on a whirlwind tour through the political developments of the Gaelic World in the late medieval era up to the Reformation in 1560: that year when, according to Archie Duncan, “all certainties were removed and all life in Scotland changed forever”. He provided an overview of the inner-workings of the Lordship of the Isles – that semi-autonomous Gaelic polity which, in 1493, was forfeited to the Scottish Crown, leaving a power vacuum in the Gàidhealtachd. Nevertheless, the speaker underlined the continued importance of Gaelic connections across the Irish Sea—for example the relationships between the Campbells of Argyll and the O’Neils and O’Donnells in Ulster. These connections were maintained in correspondence through the medium of Classical Gaelic: a high-register, literary dialect of Gaelic that bridged the gap in divergent spoken vernaculars. Despite these links, however, the Reformation would change everything.

In the 1560s, with the patronage of the 5th Earl of Argyll, John Carswell completed his adaptation of John Knox’s Book of Common Order. It was the first book to be printed in Gaelic, in either Scotland or Ireland. While written in Classical Gaelic using a Gaelic orthography, it was printed in a Roman typeface – something Ronald Black referred to as “The Carswell Compromise”. The book was intended for use on both sides of the Irish Sea. Argyll and Carswell hoped that a shared protestantism would strengthen the extant cultural and linguistic bonds between Gaelic Scotland and Ireland. The author envisaged crucial roles in the new protestant order for both the Gaelic literati and secular lords. Carswell even included a formula for blessing a ship — something of great importance to the sea-faring communities that populated the coasts of the Irish Sea.

Needless to say, this unified Gaelic-Protestant world did not pan out. Ireland remained predominantly Catholic, while many Scottish kindreds converted to Protestantism. Gaelic unity took a further hit in 1607, when the Earls of Tyrconnell and Tyrone fled for the continent – the so-called Flight of the Earls. In its aftermath, the longstanding approach of the English Crown to unruly subjects in Ireland—that of ‘surrender and re-grant’—gave way to a policy of conquest. According to Ronald, the Plantation of Ulster that followed from 1609 onwards “took the core out the Gaelic apple”, removing a crucial point of contact between Gaelic Ireland and Scotland. According to Ronald, the schools in Ireland that maintained and facilitated Gaelic language and culture went into decline, as did Classical Common Gaelic. The was more marked in Scotland, as evidenced by Martin Martin who in the 1690s remarked that the language was “such a style only understood by a few”.

In conjunction with the political effects of the Reformation, the linguistic issue would have a significant bearing on the Gaelic world. In Scotland, Gaelic-speaking ministers came to rely on the English Bible, which they would translate ex tempore into the Gaelic vernacular. This is not to say that there were not attempts to compose a workable translation of the scriptures into Gaelic.

In Ireland in the 17th Century, Archbishop William O’Donnell and Bishop Bedell produced Classical Gaelic translations of both parts of the Bible. In the 1680s, these texts were re-printed using the original Irish script. Minister of Aberfoyle, Robert Kirk, converted the text into a more familiar Roman font, in the hopes that the translation would be of use to Highland ministers. Ronald pointed out that, for this version of the Bible to gain traction, what was required was a dedicated system of schools. This, however, did not materialise. In the 17th Century, the Synod of Argyll had also made some progress. Members undertook a translation of the Old Testament into the vernacular Scottish Gaelic, but this was never printed, and the manuscript was either lost or destroyed. Despite Carswell’s pioneering translation of the Book of Common Order in 1567, Scottish Gaels would have to wait 200 years, until 1767, for the publication of the New Testament in the Scottish vernacular. Even then they would have to wait a further 34 years, until 1801, for a complete Scottish Gaelic Bible.

Ronald Black drew his talk to a close by pointing out the great irony of the Scottish Reformation. Surely, he argued, the event should have strengthened, even breathed new life into, the vernaculars of Scotland – both Scots and Gaelic. After all, it was a quintessential principle of protestantism that all peoples should have access to the scriptures in their own tongue. Nevertheless, in Scotland, both languages were relegated in favour of English. With his tongue firmly in his cheek, Ronald concluded by remarking that “we might as well have stuck to Latin”.

Our next event on 5 December is the 5th instalment of the Centre’s Historical Conversations series. The 18th Century Panel will feature esteemed scholars Allan Macinnes and Murray Pittock in conversation with Dr Stephen Mullen. Tickets are currently sold out, but join the waiting list here. We Hope you will join us.

I think it is worth stressing that this reluctance to use Scotland’s and Ireland’s Gaelic vernacular after 1534 and 1560 still leaves an active stain – the refusal of the Democratic Unionists in Northern Ireland to allow Irish Gaelic the position Scottish Gaelic and Welsh enjoy in the rest of the United Kingdom. Protestantism is still seen as an English/Lowland thing. This need not have been the case.

I think the ‘Reformation’ is better termed the’ Violent Renaissance’, but it is nonetheless interesting to imagine a united Protestant Gaelic world from Caithness to Cork where an Anglicising Protestantism had not lead to Plantation and prejudice: a still Gaelic speaking cultural entity where the word Protestant had never been rendered as Sasanach or Albanach because of the Anglicising policies of Lowland and English regimes.