On Tuesday 6th February 2018, the Centre was delighted to welcome Anne Crone (Project Manager) and Graeme Cavers (Director) of AOC Archaeology to discuss some of their findings from the excavation of an Iron Age wetland settlement at the Black Loch of Myrton. The meeting was one of a series of lectures facilitated by the Edinburgh University-based First Millenia Study Group, a discussion forum for all aspects of archaeology in the first millennia BC and AD, with a particular focus on Scottish sites.

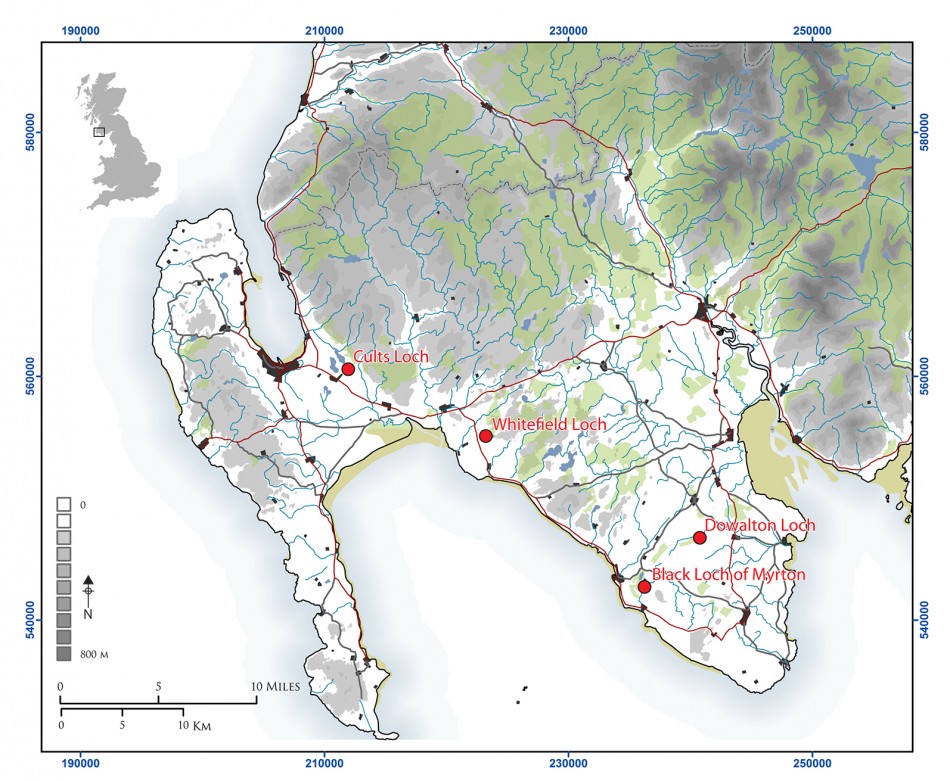

Dr Crone began the presentation with some background on the project. The site itself, situated near Monreith in the Machars of Galloway in south-west Scotland, was discovered in 2010 by a farmer performing drainage operations on the land. The site presented the opportunity to test the models and hypotheses garnered from the earlier Cults Landscape Project, which involved the excavation of several Iron Age crannogs, or artificial island settlements, in Galloway. By utilising radiocarbon and dendrochronological (i.e. analysing tree-ring patterns) dating methods, the team hoped to develop a more detailed understanding of early Iron Age settlement patterns and the structural evolution of these sites.

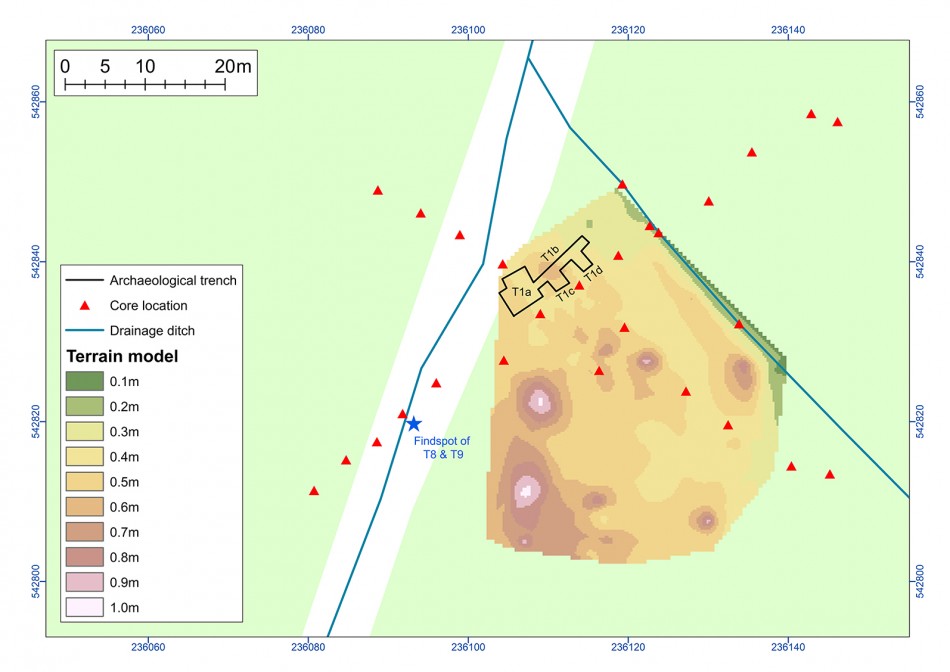

Beginning work at the Black Loch in 2013, the group are currently on their fifth (and possibly the final) season of hands-on excavation. Radiocarbon dating indicates that the settlement was likely first built in the mid-1st millennium BC. Most significantly, evidence found at the Black Loch in the course of 2013 and 2015 suggests that the settlement was not a typical crannog—i.e. an artificial island with structures constructed on top—as previously assumed. Instead the 40x60m island demonstrates the characteristics of a wetland village, or loch settlement, built directly on the boggy peat surface, with no artificial foundation around the margins of the loch in which it was situated. Thus far a unique site-type among the discoveries of archaeologists in Scotland, there are parallels to be drawn between this and similar villages at Glastonbury and Meare.

Dr Crone guided us through the excavation of 3 round houses situated on the northern half of the island, each of which survived as a mound. She also identified 3 episodes of settlement activity. The basic structure of these dwellings was provided by thick wooden posts, while numerous sturdy wooden beams in the interior suggest that the indoor space would be subdivided. At the centre of each construction was a hearth, indicated by mounds of cobbles on top of clay. The floors were constituted of a foundation of branch-wood bundles beneath compacted layers of plant-litter, mostly bracken and sedge.

We cannot be certain of the duration of occupation in these houses, with estimates ranging from only 3 years, up to a possible 40 years. It does, however, appear that the houses were occupied repeatedly, on a temporary, possibly seasonal, basis. This is evidenced by apparent refurbishment efforts, including the setting of new floors and hearths with each occupation. Furthermore, only a small number of stone tools were found on the site, suggesting that the houses were not used for long-term storage. Alterations were also made to the entrances, with some incorporating thick oak beams. This was possibly done with an eye to impressing guests and travellers, as we are now aware that at the time of one tree’s felling in 435 B.C., oak was very uncommon and therefore valuable. Finally, our speaker discussed refurbishments to the defensive perimeter possibly carried out at a later date in the 4th or 3rd century B.C., including the erection of an oak-post palisade and ramparts.

Dr Crone concluded the presentation with a summary of objectives for the future of the project. First, the team hope to make more sense of some of the more unique features uncovered in these dwellings, for example several unfixed trays found at floor-level, which may have been used for food storage. Secondly, to establish with more precision the timespans between episodes of settlement activity. And finally, to explore in greater detail the patterns of settlement, reoccupation and refurbishment. We look forward to hearing more from Anne and Graeme in the future about this project, the discoveries of which may have profound implications for our understanding of Iron Age settlement in Scotland, Britain, and further afield.

Our next seminar on Tues 13 February features Prof. Alan Riach of ScotLit who will discuss the translation of two landmark Gaelic poems from the 18th Century: Alasdair Mac Mhaighstir Alasdair’s Birlinn of Clanranald and Duncan Ban MacIntyre’s Praise of Ben Dorain. We hope you will join us.