On 25 February 2014, the Centre welcomed Professor Dauvit Broun to discuss ‘How British is Scotland? Britain and Scottish Independence in the Middle Ages’. This continued the ongoing ‘How British is Scotland?’ mini-series. Below is this listener’s brief summary of the lecture.

Elaborating on many of the ideas and themes from his recent Inaugural Lecture, Prof. Broun engaged in an expansive exploration of Scottish (and British) identity from the Picts to fourteenth and fifteenth century Scotland (and beyond). He began by outlining what he was not going to talk about: Scottish independence and identity through the prism of the Wars of Independence. The well-trodden ground of the Declaration of Arbroath was left to the side. Instead, his lecture was divided into three main sections, all exploring how much ‘Britishness’ mattered to medieval Scots.

The first theme discussed how the sharing of the island of Britain intrinsically created a pan-British identity. But while the island unified, Scots consistently sought to emphasise their distinctiveness within the landmass. In John of Fordun’s Chronica Gentis Scotorum (which was largely based on an earlier text) the author muses on a proposed Union of Crowns between December 1383 and August 1387. He states ‘these two royal lines’ (of Scotland and England) were to be ‘joined as one, in the person of one prince’. However, this ‘prince’ was a member of the Scottish royal family, descended from St Margaret, making the true heir of the English throne a Scot. A poem by Thomas Barry in c. 1388 detailing the Battle of Otterburn, again espouses an idea of Britishness based upon the island itself: the ‘island home of the British contains two most warlike kingdoms’ (Scotland and England). Again, the two kingdoms are distinguished from each other.

Prof Broun then explored a second, related theme focusing on the pan-British aristocracy. Many Scottish nobles were ‘cross-border lords’ who held substantial lands in England. Most originated from France and maintained a simultaneous English, French and Scottish identity (some could even speak Gaelic through intermarriage with families from the south-west of Scotland). Robert Bruce comfortably invoked English common law during his reign, which may seem ‘outrageous’ to a modern audience but was natural at the time. At the Battle of Lewes in 1266, representatives from the great noble families of Scotland, the Balliols, the Comyns and the Bruces, boosted Henry III’s forces in his struggle against the usurper, Simon de Montfort. In the Chronicle of Melrose, Guy de Balliol is described as a Scot proud to die for ‘England’s justice’ at the Battle of Evesham.

Despite this integration and association with England, these nobles did not want Scotland to be wholly subsumed by their neighbour. They paid 10,000 merks to rescind the Treaty of Falaise (made between the captured William the Lion and the English king, Henry II) which threatened the interests and independence of the Scottish king and kingdom. Earlier, they had refused to raise a similar sum to fund a Crusade to the Holy Land, showing they were prepared to pay up when it was in their interests to do so. Scottish nobles stressed the distinctiveness of Scotland, notably in the language of charters, because changing law practice in England made it increasingly difficult to control landholdings. Furthermore, the English court was becoming more and more accessible to the humblest subjects: some Scottish nobles were resistant to this trend. Stressing the uniqueness of Scottish law and custom was a way of safeguarding their interests.

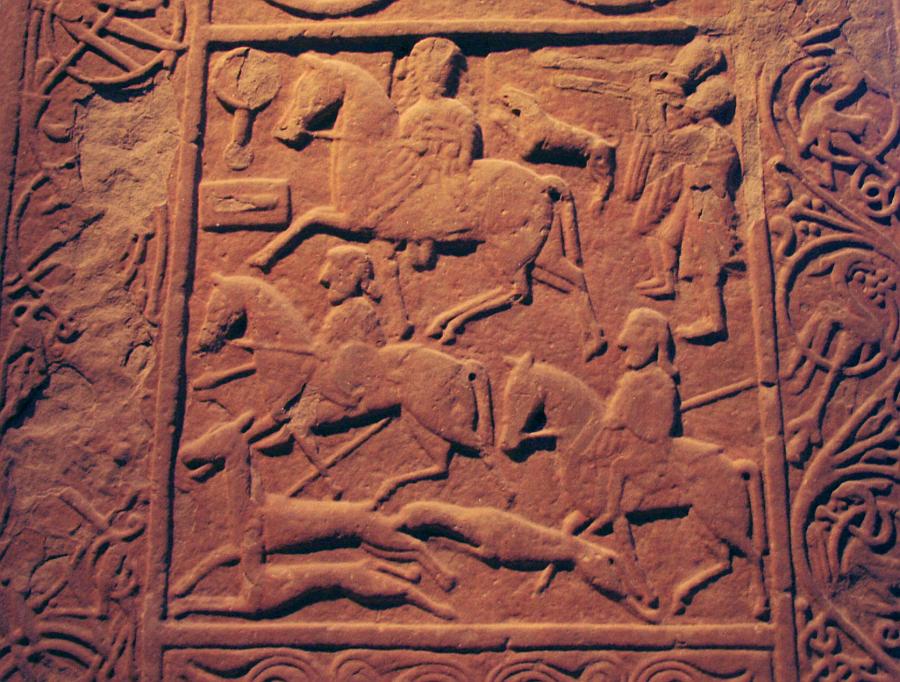

The third theme analysed by Prof Broun revolved around Pictish identity, particularly in the word ‘Alba’. Before 500, Alba meant ‘Britain’ but in the centuries that followed it became associated with the landmass north of the Forth. It has been suggested that ‘Alba’ was meant to refer to Gaelic Britain, but it seems more likely that it was a Gaelic rendering of Pictland before the tenth century. The physical barrier of the Forth cut off Pictland from the rest of Roman Britain. The principal method of traversal was by boat across the Firth of Forth, which may have added to this feeling that Pictland was a new island, accentuated further by the presence of Antonine’s Wall. Through their sculpture, which featured unique symbols and script, the Picts may have been attempting to distinguish themselves from the rest of Romanised Britain. To take this further, they self-identified as an ‘alternative Britain’, or even ‘Britain par excellence’–they were not merely a ‘part’ of the island. The Gaelicisation of Pictland was not inimical to Pictish identity but provided another way of emphasising distinctiveness from the rest of Britain.

The over-riding concern throughout all of these themes across the middle ages was the separateness of Scotland, even within a wider pan-British identity. The idea of Britishness was not–is not–uniform. On some issues the different identities converge, on others they diverge, and Professor Broun suggested that this year’s referendum offers the chance to assert a sense of Britishness distinct from that offered by Westminster.

Summary by Ross Crawford (PhD Researcher)

The Centre seminar series continues on FRIDAY 28 FEBRUARY. The rescheduled Angus Matheson Memorial Lecture by Professor Mícheál Ó Mainnín (Queen’s University, Belfast) ‘The North-West Channel: Ireland and the Book of the Dean of Lismore’ will be held in the Lecture Theatre, Sir Alexander Stone Building, 16 University Gardens at 5.30pm. Tea and coffee outside the lecture theatre from 5pm. Wine reception after lecture in 3 University Gardens. All welcome.