On 10 January, 2017, the Centre welcomed Fabrice Bensimon (Université Paris-Sorbonne) to discuss ‘Scottish workers in France, 1815-1870’. In his lecture he focused on the experiences of the approximately 1,000 – 1,500 linen workers from Dundee that emigrated to France from 1815-1870. He discussed the practicalities of migrating to these areas to work in linen factors, their experiences of integration and xenophobia, and the other social complexities that they encountered. Below is this listener’s summary of the lecture.

Fabrice began by saying that, during the period of industrialization, Britain had the technical advantage over most countries in Europe. Often Britain’s workers were recruited to impart their knowledge of their respective industries to train Continental workers in the use of new machinery. More extensive research has been done studying the emigration of British peoples to faraway places, like the United States and Australia, and very little has addressed British emigration to Europe. This is largely because more historical documents exist for these long-distance trips than for shorter trips to the Continent, but also because in most cases, emigrating British people integrated into their new communities. In this seminar, Fabrice discussed his work studying the immigration of Scottish workers to different areas of France and their influence on France’s linen production from 1815-1870. He outlined the types of sources that he relied on in this research, he described Dundee’s linen and jute industry connections to France, discussed how Dundee emigrants were recruited to work in France, provided evidence for the degree to which the Scots integrated, and concluded with a description of emigration politics and the 1848 Crisis.

Fabrice began by saying that, during the period of industrialization, Britain had the technical advantage over most countries in Europe. Often Britain’s workers were recruited to impart their knowledge of their respective industries to train Continental workers in the use of new machinery. More extensive research has been done studying the emigration of British peoples to faraway places, like the United States and Australia, and very little has addressed British emigration to Europe. This is largely because more historical documents exist for these long-distance trips than for shorter trips to the Continent, but also because in most cases, emigrating British people integrated into their new communities. In this seminar, Fabrice discussed his work studying the immigration of Scottish workers to different areas of France and their influence on France’s linen production from 1815-1870. He outlined the types of sources that he relied on in this research, he described Dundee’s linen and jute industry connections to France, discussed how Dundee emigrants were recruited to work in France, provided evidence for the degree to which the Scots integrated, and concluded with a description of emigration politics and the 1848 Crisis.

The records Fabrice utilized in his research mainly consisted of state records, newspaper articles, private documents (such as memoirs, diaries, and letters), and consular letters. He said that although there were few state records, both the British and French sides were concerned about foreigners, especially from 1815-1830, so some records do exist. Local newspapers reported on foreign arrivals, especially when they arrived in groups. Emigrants exchanged letters, and some even wrote autobiographies on their excursions abroad (one example given was “The Life and Adventures of Colin,” a man from Leith who went to the Continent, became a drunkard, and consequently became a teetotaler). Correspondence between consuls offered insight into the mediations that took place between British authorities and the British who were living on the Continent.

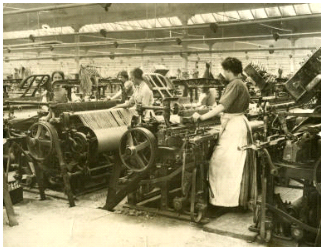

In his description of the Dundee Linen and Jute industry, Fabrice discussed the advancements that aided in the production of linen in Britain, especially water and steam-powered machinery. By the 1830s, France’s linen producers had supported high tariffs on imports to protect their local linen industry. This encouraged British linen manufacturers to form partnerships with French linen producers to aid in avoiding tariffs. In addition to these partnerships, by which French companies obtained advanced British machinery, French linen manufacturers encouraged British workers to immigrate to France in order to train their local workforce.

The majority of workers in the Dundee linen industry were women who were employed as spinners. Unfortunately, once the woman turned 18 years of age, they were laid off, which forced them to look for work elsewhere. The Continent was a prime opportunity for these highly-skilled workers, especially with the offer of higher wages. Male mechanics were also recruited by Continental linen companies. These workers were recruited by word of mouth, agents who specialized in this field, and through advertisements in the newspaper. While Fabrice estimated that about half of the Scots that emigrated to France for work during this period eventually returned to Scotland, it is evident that even those who stayed for an extended period of time kept strong social connections with those back home. A Scotsman who worked in France as a manager for twenty-five years still published news of the death of his child in a Dundee newspaper. Presbyterian Scots often had to choose between converting to Catholicism or traversing back to Dundee in order to be married to their French-Catholic significant others.

Fabrice stated that the Scots integrated into their local communities to differing degrees. Early in this period, most local newspapers looked upon them favorably and appreciated that they were training their local workforce. However, the 1848 crisis resulted in demonstrations and riots that targeted all foreigners, including the Scots and British. These riots took place in the context of joblessness, in which local workers wanted to have the jobs of their foreign counterparts. By this point, the foreign female workers had their working hours and pay decreased, and they were being replaced by Flemish workers. Fabrice shared several letters from British migrant workers asking for aid from British officials to return to Britain. This political climate forced many of the migrant linen workers to return back to Britain, while others sought work elsewhere.

Summary by Megan Kasten (PhD Researcher)

Our seminar series continues next week on 17 January 2017 with Adrian Maldonado (University of Glasgow) to discuss ‘Pop Culture Picts and the Imaginary Hadrian’s Wall’. This will be held in Room 202, 3 University Gardens at 5.30pm. All welcome!

Thank you, Megan, for a precise but very informative summary. Being an amateur genealogist and therefore very interested in social history I found this very interesting, given that I had not heard of the movement of workers to France,

Marjorie