On 28 November, 2016, the Centre welcomed Cathy Swift (Director of Irish Studies in Mary Immaculate College, University of Limerick) to discuss ‘Early Irish Migrations to Scotland – Difficulties, Debates and DNA.’ Diasporic peoples are becoming increasingly interested in where their ancestors came from, especially people from the United States and Australia. Recently, DNA analysis has become more affordable and has entered the realm of popular science and genealogy. In her paper, Cathy highlighted several issues with the methodology behind a recent study that used DNA analysis and argued that genetic studies focusing on historic population movements must utilize many strands of evidence, including detailed historical information and linguistic evidence, to ensure that their arguments are properly contextualized.

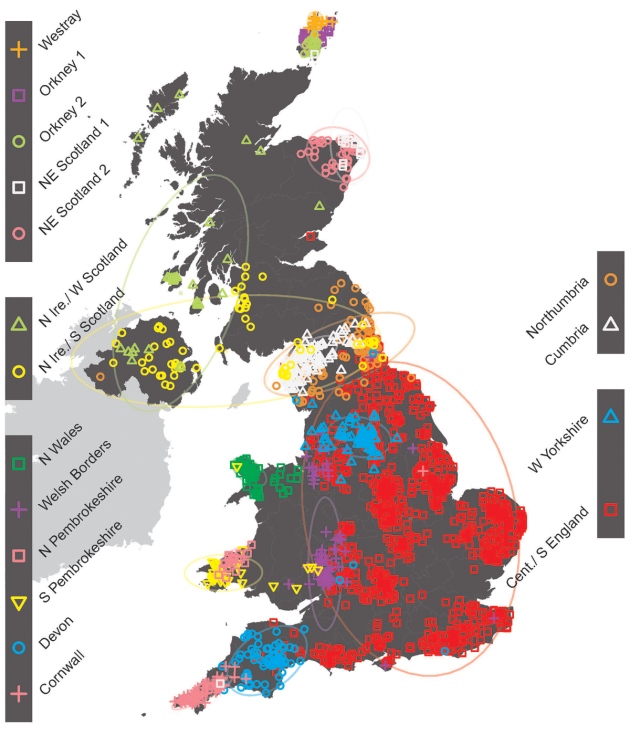

Image taken from the original article in Nature: doi:10.1038/nature14230

Cathy began by giving a general overview of the historiography of the movement of people between Britain and Ireland, where she emphasized the importance of placenames, archaeological evidence, linguistic patterns, and historical narratives to this area of research. She argued that throughout history, national histories inevitably become nationalist histories that are always influenced by their modern political context.

The study of historic population movements through DNA analysis is still a relatively young discipline; one of the earliest studies undertaken by Trinity College Dublin in 2000 studied the initial spread of farming by comparing DNA profiles between people from Turkey and Connacht. In these early DNA research projects, very few people were tested due to the cost and fewer markers were studied. Now, the cost of DNA testing has decreased and the number of markers taken into account has increased. Even though data collected from recent studies is completely different from the information collected from earlier studies in DNA analysis, Cathy argued that conclusions from earlier papers are not viewed with as much skepticism as they should be; these earlier studies are based on a completely different, less-detailed dataset. While the study of the DNA markers associated with surnames was of interest in the early stages of academic genetics, recently the study of the genetics of surnames and surname groups has become popular on the Internet and in the commercial realm.

Recently an article entitled “The fine-scale genetic structure of the British population”, published in Issue 519 of Nature, on 19 March 2015, gained a great deal of attention in the media. The aim of their study was to look at fine-scale genetic variation in the British population in relation to historical demographic events. Their sample size came from volunteers who knew where all four of their grandparents were from; a mean calculation of distance was derived from this information and this resulted in the “dots” on the map. They found “a rich and detailed pattern of genetic differentiation with remarkable concordance between genetic clusters and geography.” However, Cathy voiced many concerns over the main assumptions of the study and that one of its primary conclusions, the lack of evidence for a ‘Celtic’ population in Britain, was strongly motivated by modern politics.

One of Cathy’s concerns was that Ireland was not included in the original study. The authors of the article stated that Ireland was not included in the study because the sharing of ancestry with Ireland could reflect British migration into Ireland. Swift found it odd that this sharing of ancestry might not reflect Irish migration into Britain. The authors also stated that shared ancestry between European and British populations represented European populations migrating into Britain, either just after the Ice Age, the Roman incursion into Britain, the Anglo-Saxon migration, or the Vikings settling in Britain. Cathy pointed out that this shared ancestry might also reflect British migration into Europe, but the authors do not take this into consideration. This inconsistent treatment of shared ancestry with Ireland and Europe throws into sharp relief the strong political underpinnings of the assumptions of the article. The authors also failed to test a large area of Britain; clearly Scotland is underrepresented in the study. Finally, Cathy expressed that, most of all, she was disappointed with the authors for concluding that there is a lack of evidence for a Celtic population in Britain, especially because the overwhelming evidence for shared ancestry with France in areas which speak Celtic languages might indicate the trace of a Celtic population.

Apart from the issues raised above, Cathy also suggested that the researchers that wrote the article did not do enough specific historical research. Although the article emphasizes its historical significance, they list very few archaeological and historical sources in their bilbiography; those that they do list are very generalised sources. The authors also suggest that most of the variation in the population took place somewhere between the migrations of Saxon of 500 AD to 16th century Ulster plantations. This article assumes that there was not much moving around apart from mass-migrations before the Industrial revolution, which Cathy knew from her own research was not the case.

Her study of the family of Henry Blund, who was archbishop of Dublin from 1213 – 1228 and was known as Henry of London, is a prime example of movement during the 12th and 13th centuries. Several of his brothers took turns as the Sheriff of London for several decades, while he established himself in Dublin. Due to the status of his new position, he was able to give his nephews positions within the church and arranged for his niece and nephews to marry into important landowning families all around Ireland. However, Blund also appears to be a very popular surname in the 1200s. If someone was blonde-haired, it became fashionable to refer to them as Blund, or Albus (white), so people sharing the same surname might not be even remotely related. Clearly the populations of the 12th and 13th centuries were more mobile than was suggested in the Nature article.

In conclusion, Cathy quoted Catherine Nash, who stated that “genetic maps of difference and degrees of relatedness quickly become material for the making and revision of national and diasporic ethnical connections.” These debates on historical population movements have been influenced by nationalist thinking; those projects which claim to be scientific need to be especially rigorous in their methodology. In this case, Cathy concluded by saying that the project’s validity is undermined by inconsistent treatment of migration with different landmasses and the lack of historical research.

One can gain access to the original Nature article from which our readers might be able to draw your own conclusions here.

Summary by Megan Kasten (PhD Researcher)

Reading Doug Orr and Fiona Ritchie’s wonderful book, “Wayfaring Strangers,” I’m tempted to reply “follow the fiddle!” History is the story of immigrants and refugees. Thanks, Jo